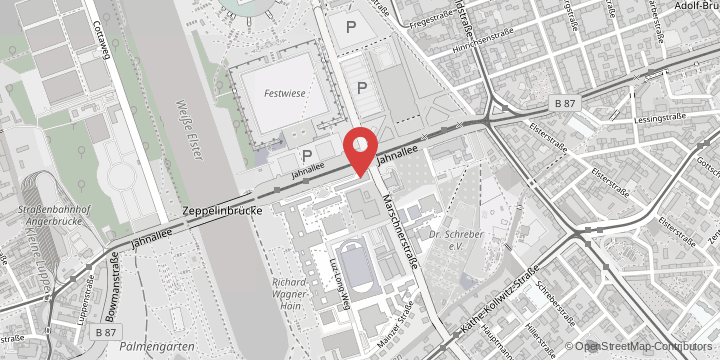

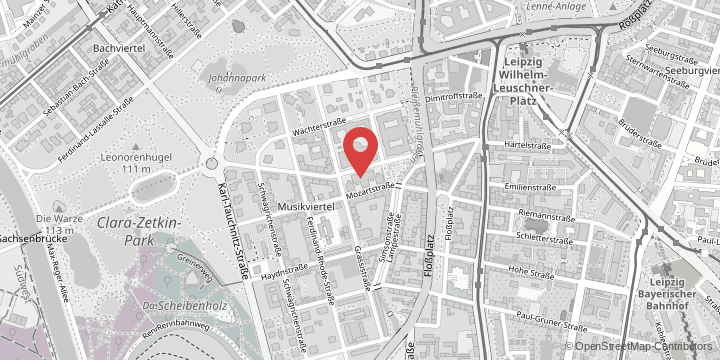

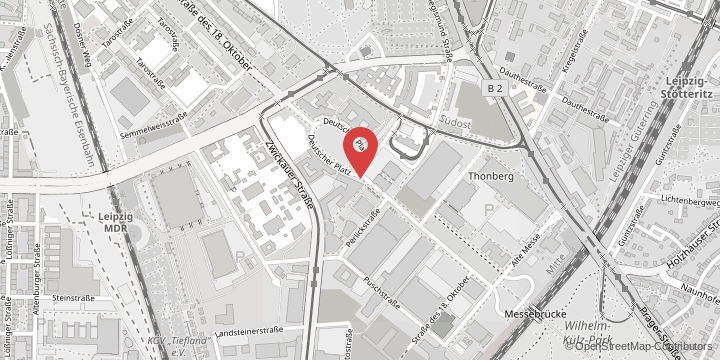

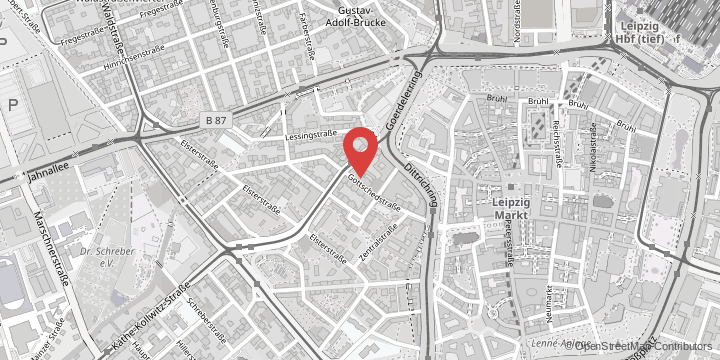

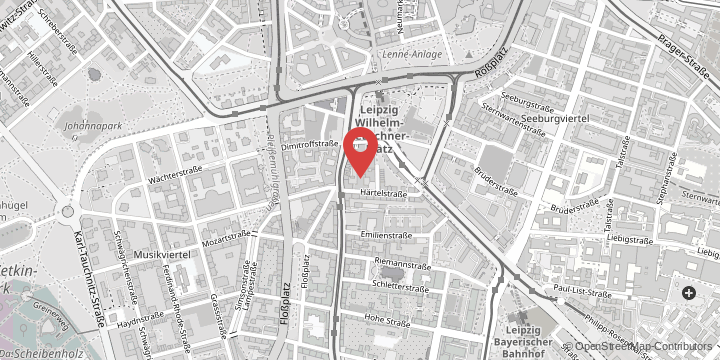

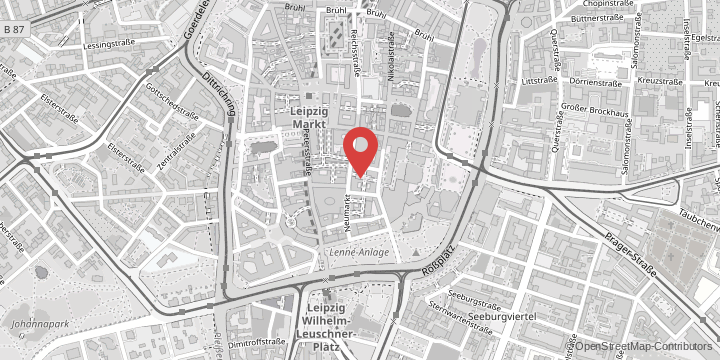

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is a common condition, affecting one in every 2500 births. Up to 30 per cent of affected babies die from it. The main problem is the underdeveloped lung. The condition also involves a hole in the diaphragm, which paediatric surgeons correct by closing it in the first week of life. Until now, there has been little medical knowledge about how CDH develops – what exactly goes wrong during embryonic development. Dr Richard Wagner, a paediatric surgeon and scientist at Leipzig University Hospital, teamed up with researchers from Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston to establish a new patient-specific cell model at Harvard Medical School. Using their model, the researchers investigated possible ways of treating this condition.

Babies with CDH are placed on a ventilator immediately after birth. “We were able to isolate stem cells from the fluid that is sucked out of the children’s lungs and otherwise disposed of, and grow them in the laboratory,” explains Dr Wagner, first author of the study. While working as a postdoctoral researcher in the US, the doctor from Leipzig examined the stem cells in the laboratory together with the American researchers, designing cell models of the airways of the tiny patients. This gave them access for the first time to “living” human lung tissue from patients with CDH. They then compared the stem cells from healthy and underdeveloped lungs.

Goal of treatment during pregnancy

When the researchers looked at the molecular properties of the stem cells, they found that they had been altered due to inflammation. However, drug therapy in the cell model was able to restore functionality. “We also tested this process in animal models and showed that the treatment contributed to better lung development there, too. With the same drug therapy, we were therefore able to achieve positive effects both in human cells in the Petri dish and in the living organism in the established animal model,” explains Dr Wagner.

The treatment was performed with the steroid dexamethasone. This drug is already used in clinical practice to induce lung maturity in the foetus when there is a risk of premature birth during pregnancy. “What is most appealing is the fact that we already know that this drug is not harmful in pregnancy. If we were to collect more data in laboratory research, it would be possible to investigate later in clinical trials whether there are advantages to administering the drug during pregnancy in order to slow down the possible inflammation in the organism and help the lungs grow,” says Dr Wagner, adding that the aim in future is to be able to intervene with a drug directly after the diagnosis of a diaphragmatic hernia, which happens at around the 20th week of pregnancy.

Original publication in American Journal of Respiratory und Critical Care Medicine:

“A Tracheal Aspirate-Derived Airway Basal Cell Model Reveals a Proinflammatory Epithelial Defect in Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia”, Doi: https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202205-0953OC