South Africa is currently experiencing an unusually cold winter. At the same time, the country has to contend with power cuts that just keep getting worse. What impact do the power cuts have on public life at the moment?

The power supply in South Africa is an issue that paradigmatically illustrates many structures of this post-apartheid society.

There have been regular power cuts since 2007, which the government euphemistically calls load shedding. At the same time, the Electricity Supply Commission (Eskom), the state-owned electricity producer, was named Energy Producer of the Year at the Global Energy Awards in New York in December 2001. After the first power crisis in 2007/08, there were further power cuts in 2014/15 – and since 2019 this has become the permanent situation.

Currently, depending on the region of the country, there is no electricity for a total of between seven and a half and ten hours a day for private households, but also for companies and, for example, restaurants, as well as – particularly alarming – for 80 per cent of the public health care system. Rural areas and townships are usually more affected than middle- and upper-class suburbs. Last year, there were 200 days without a stable power supply, compared to 48 days in 2021. Incidentally, almost 30 years after the first democratic elections in 1994, a good 15 per cent of people in South Africa still have no access to electricity at all.

On 6 March 2023, President Cyril Ramaphosa appointed a Minister of Electricity within the Presidency, and on 5 April 2023 the government declared a state of disaster as a result of the ongoing electricity crisis.

What causes the power cuts?

Well, it’s complex. There are two overarching causes. First, the energy infrastructure is outdated and the necessary reinvestments have been delayed for decades. Fourteen of the 17 power plants were built before the end of apartheid in 1994. Some of these power plants have since collapsed and are simply out of commission. At the same time, Eskom is carrying a debt burden of more than €21 billion. And South Africa is still more than 94 per cent dependent on fossil fuels. Second, and at least as important, the collapse of the power supply is part of a larger complex of corruption, theft and in some cases active sabotage. Those involved include, or included, factions of the ruling African National Congress (ANC), the Indian-born Gupta brothers (who have since left the country), Mafia syndicates and foreign companies. Under President Jacob Zuma, who governed the country between 2009 and 2018, these groups appropriated state-owned enterprises (e.g. railways, the national airline SAA, the freight transport company Transnet and power generation) with the goal to systematically embezzle from them – commonly discussed under the catchphrase state capture.

This complex of crimes has been detailed in six extensive reports between August 2018 and June 2022 by a Commission of Inquiry headed by then Deputy Chief Justice Raymond Zondo. The economic damage is estimated at about €25 billion. The Eskom chief executive, André de Ruyter, who resigned early in February 2023, calculates the damage to the energy infrastructure, which continues to be caused by theft, at a good €50 million per month. In a book, he claims that the four groups taking the money for themselves have connections all the way to the government and President Ramaphosa. De Ruyter no longer lives in South Africa after an attempted cyanide attack. Foreign companies are also involved in the looting of state-owned enterprises, as the case of Asea Brown Boveri (ABB) Ltd. shows. The Swiss plant manufacturer used huge bribes to get contracts in South Africa – most notably the construction of the Kusile coal-fired power plant in Mpumalanga province (2015) – and later contributed to bleeding the state dry through hugely inflated invoices. In December 2020, ABB and Eskom agreed to repay about €100 million to the South African power producer; two years later, ABB agreed to a further settlement and the payment of a €150 million penalty to the state treasury.

How do the power cuts affect the economy?

The effects of the power cuts are complex. They range from production losses and falling revenues in the private sector to job losses (2021: minus 350,000), but also to increased theft and burglary rates (since, for example, the ubiquitous surveillance cameras and other electronic security systems don’t work when there isn’t power). In addition, other basic service systems are at risk of being damaged. In spring 2023, water treatment and filtration systems collapsed in some places; water supply to the country’s central plateau with the industrial belt around Johannesburg depends on large electrically powered pumping systems that function. In July 2023, the water supply in large parts of this province had to be greatly reduced or even completely shut down for several days as a result of maintenance and repair work.

Economically, South Africa has now gambled away almost all of its credit. In March 2023, Standard & Poor, the third of the major credit rating agencies, followed suit and rated the country’s creditworthiness as BB–, similar to Fitch’s rating in December 2021. South Africa is thus considered a risky location for foreign investors.

What long-term consequences do you expect for South Africa as a result of the blackouts and Mafia structures?

According to the Africa Organized Crime Index (Pretoria and Paris), South Africa is firmly in the grip of a small number of Mafia syndicates that are closely intertwined with local and national politics. At the same time, the judicial process of state capture is very slow. Most of the politicians and managers accused in the Zondo Commission reports are still at large. At least the former executive director of Eskom, Matshela Koko, has been in custody since August last year. And an injunction of €29 million has recently been issued against former South African ABB managers and their immediate family members.

As always, there are a lot of shadows in South Africa on this issue, but there is also light – namely the hope that the independent judiciary, the highly resilient civil society and the vigilant quality press will hold to their moral compass, something that ANC has long lost sight of. Economically, however, the country will have to be prepared for very difficult challenges in the foreseeable future.

And politically, the already strained social cohesion in South Africa could worsen as a result. In the face of multiple crises, the various (mostly left-wing) political populists have had ever more success in mobilising destructive and xenophobic sentiments. Moreover, elections will be held in spring 2024, in which the ANC could lose its absolute majority for the first time since 1994. The possible consequences of a coalition government or a tolerated minority government are currently a subject of controversy.

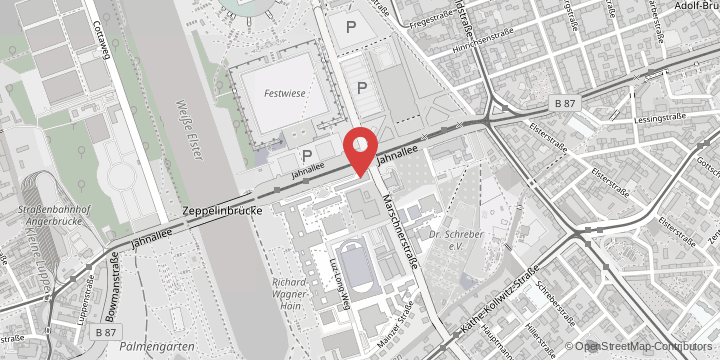

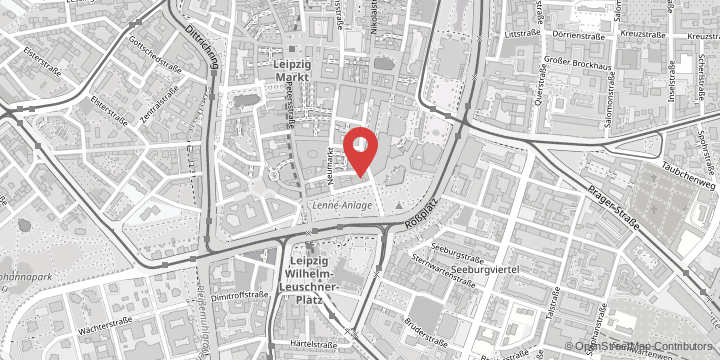

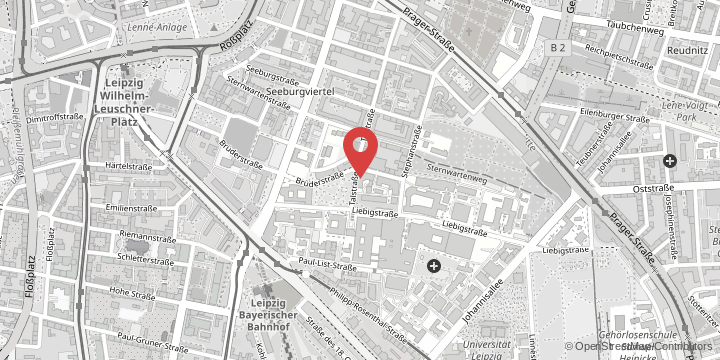

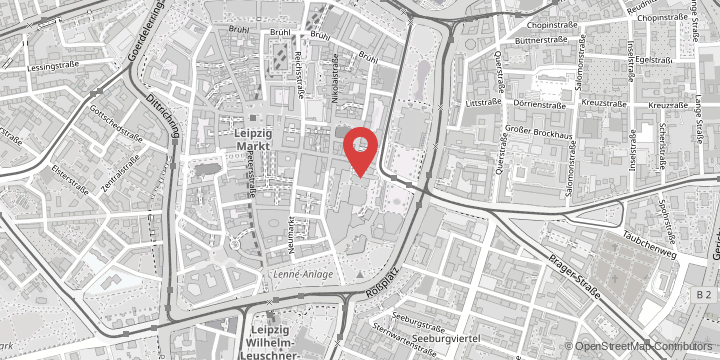

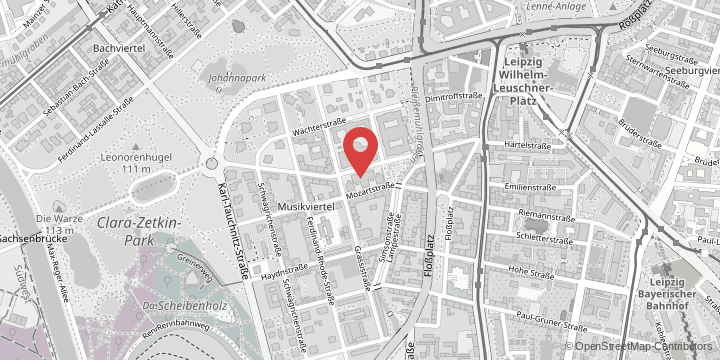

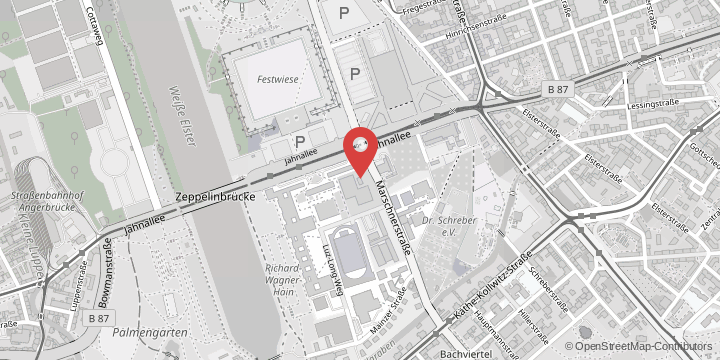

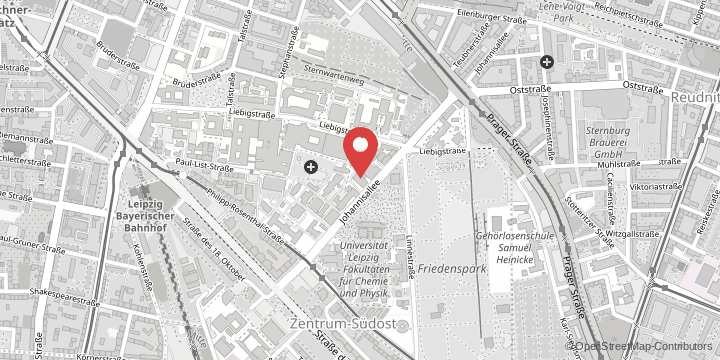

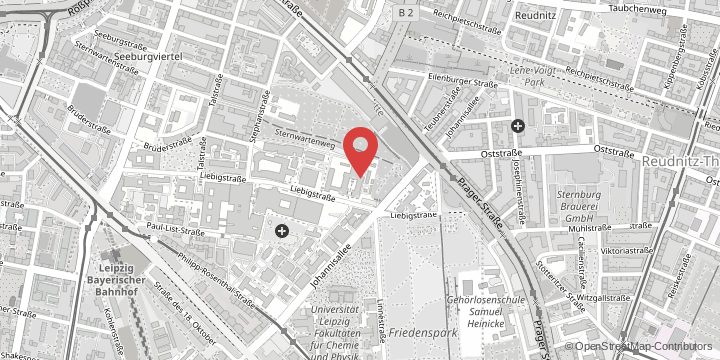

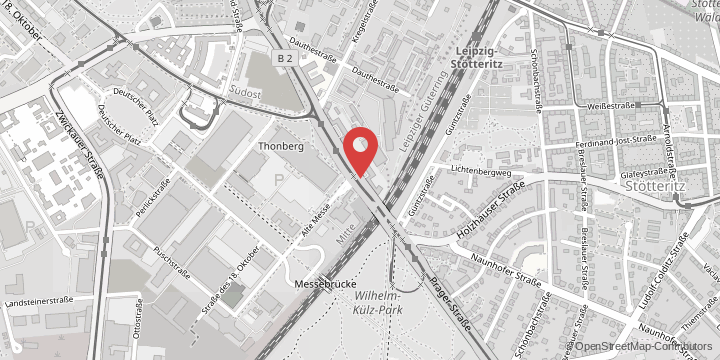

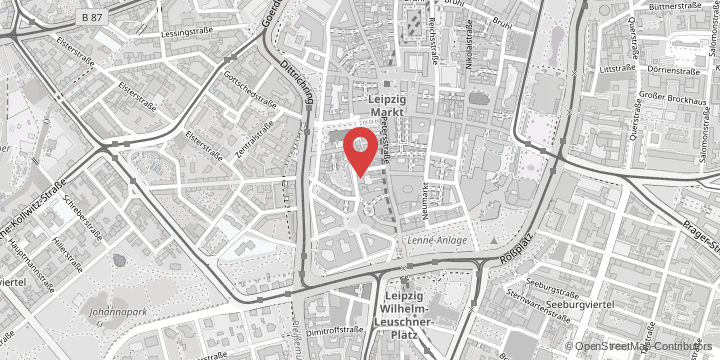

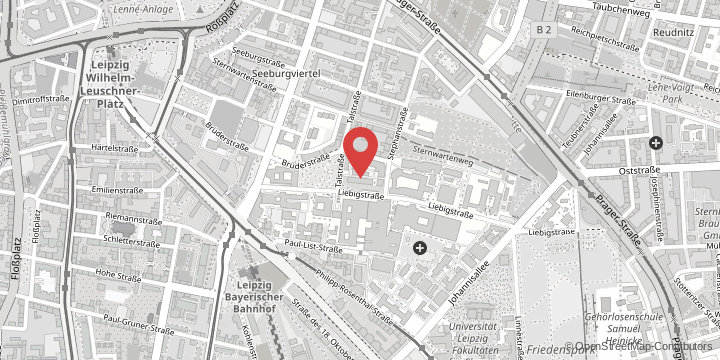

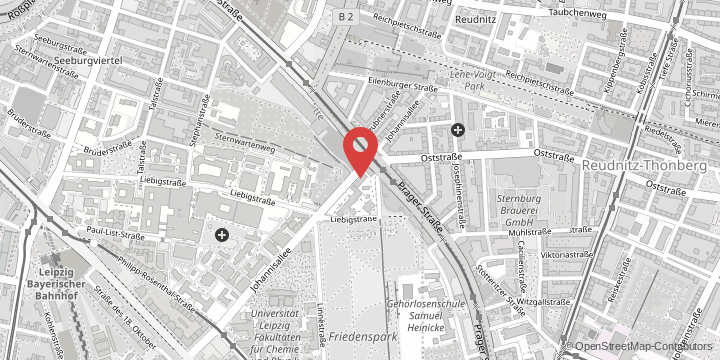

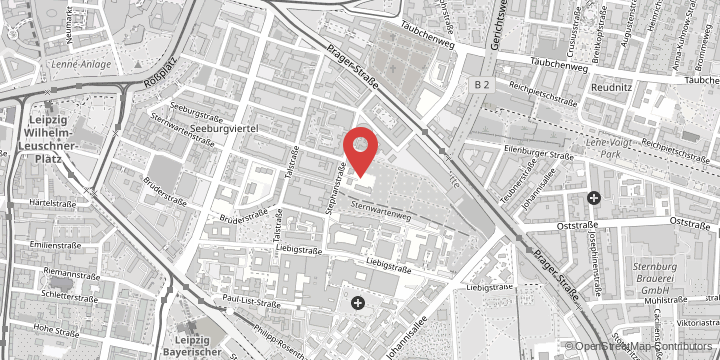

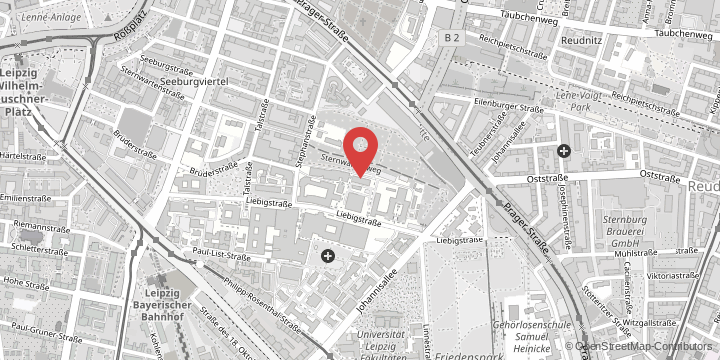

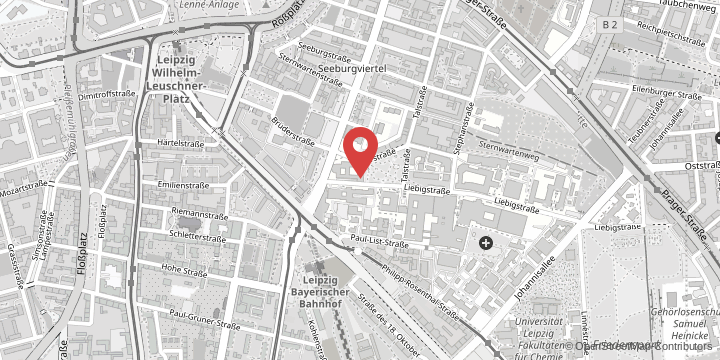

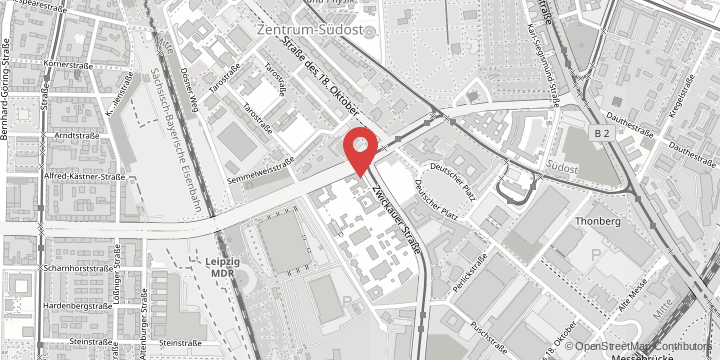

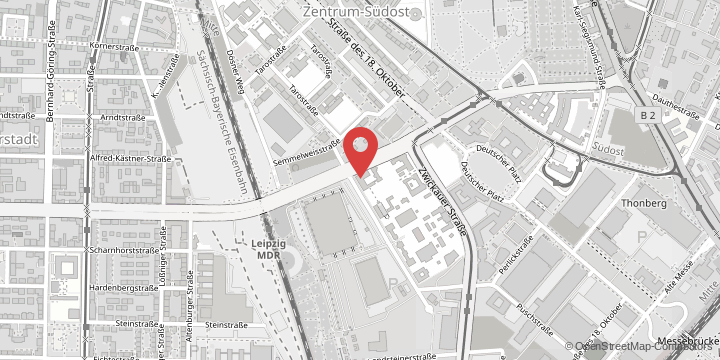

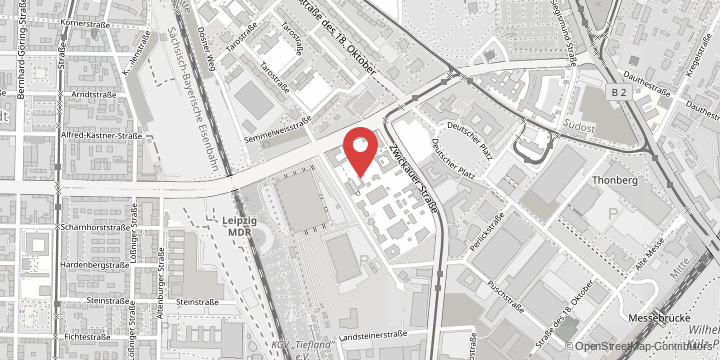

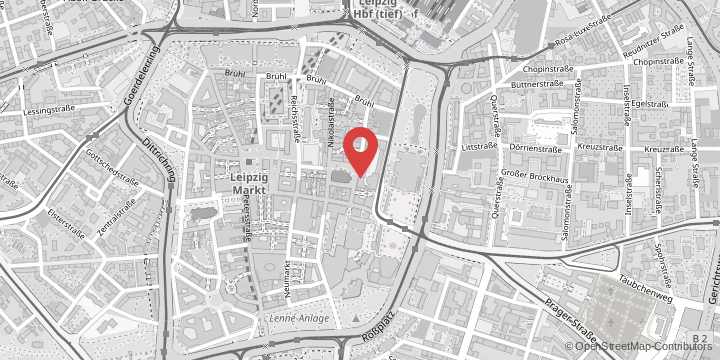

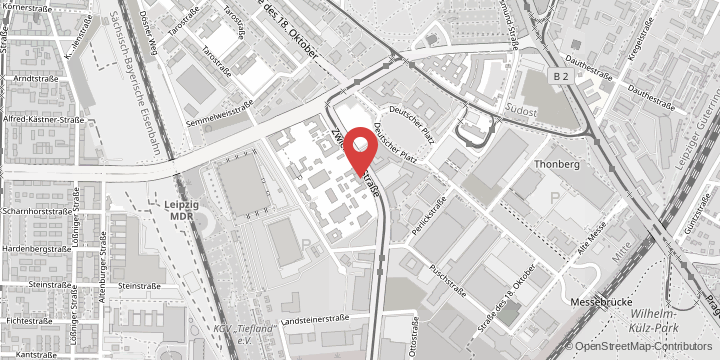

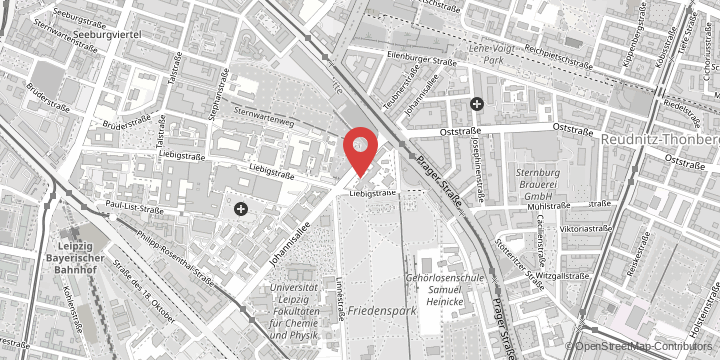

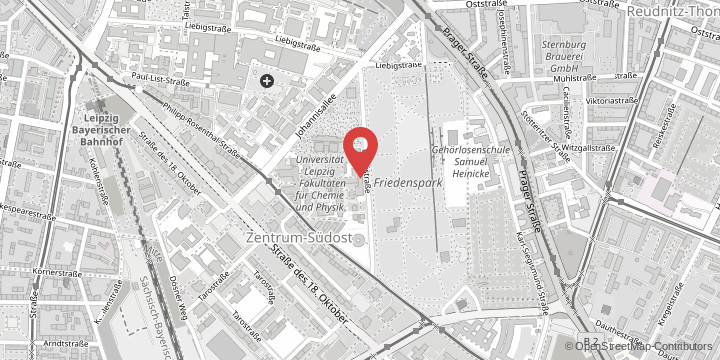

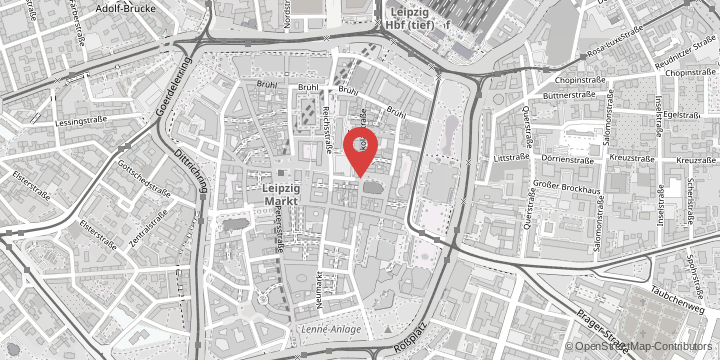

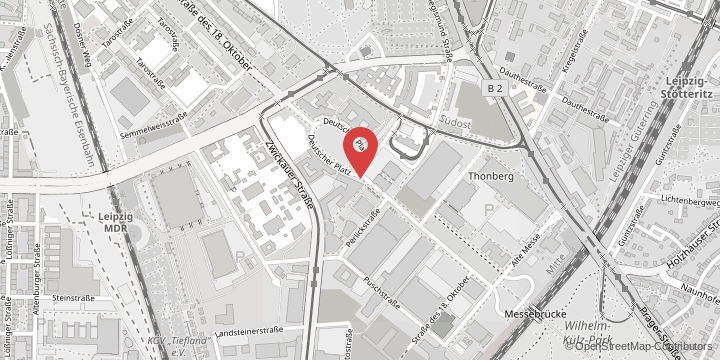

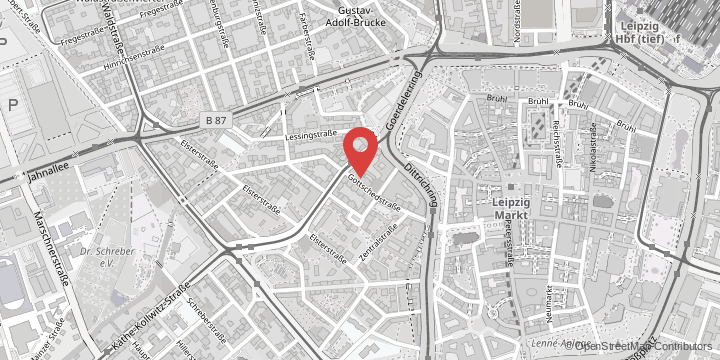

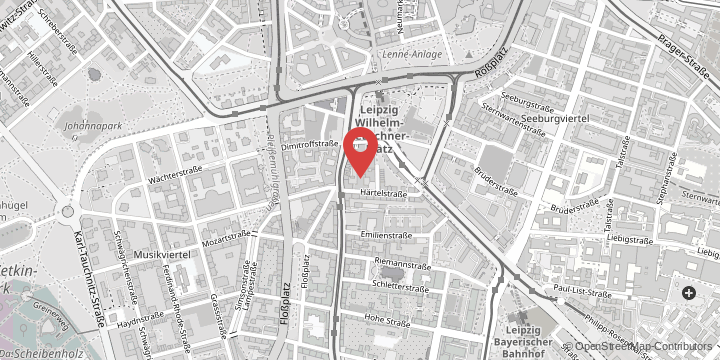

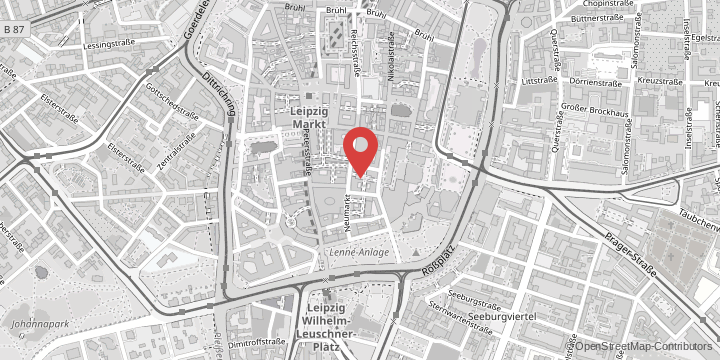

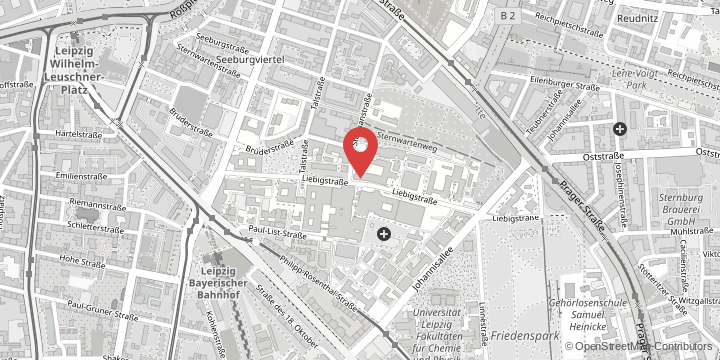

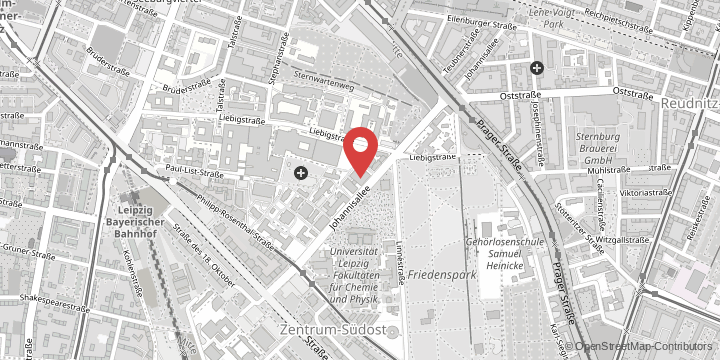

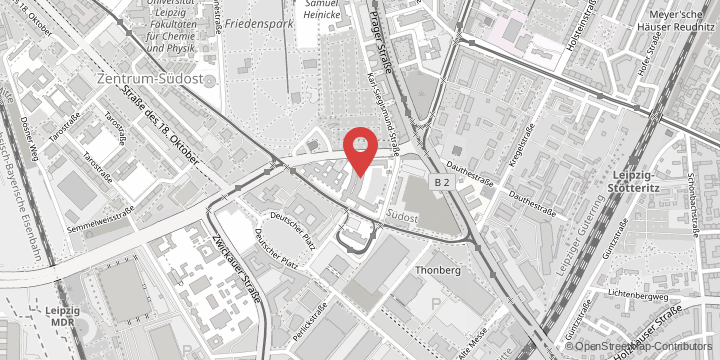

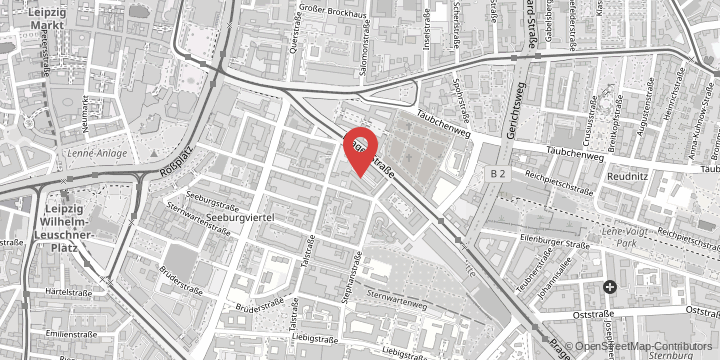

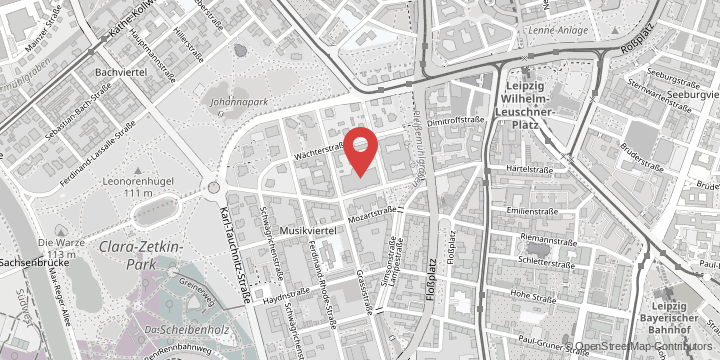

- Ulf Engel is a professor for politics in Africa at the Institute of African Studies at Leipzig University. He is also professor extraordinary in the Department of Political Science at Stellenbosch University in South Africa and a visiting professor at the Institute for Peace and Security Studies at Addis Ababa University. Through the Research Institute for Social Cohesion (FGZ) funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), Engel heads the research project Political Populism in Southern Africa: Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe (2021–24). He is also involved in the New Global Dynamics research project in the second competitive phase of the Excellence Strategy of the federal and state governments.