ReCentGlobe’s annual conference asks about the future of globalisation in the shadow of profound change. Your panel will consider developments in Africa. What challenges do African states face as a result of recent global crises such as the Ukraine war?

One result of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine is the imminent loss of one of the world’s largest producers of wheat and sunflower oil, as well as a global increase in prices for these foodstuffs. Individual states on the African continent, such as Egypt or Ethiopia, are highly dependent on these imports. They face the threat of significant price rises for basic foodstuffs, social protests and hunger. However, key global commodity chains are also facing an overall stress test. This also has implications for the African Continental Free Trade Area AfCFTA, launched on 1 January 2021.

At the same time, the demand for energy is increasing in Europe in particular. Countries such as Ghana, Mozambique and Tanzania, which are getting into liquefied natural gas (LNG) production, face the challenge of making productive use of this potential wealth – and not falling into the trap of the so-called resource curse. This situation has already been faced in the past by numerous authoritarian states – from Nigeria to Sudan – whose oil wealth has benefited only a small corrupt elite.

In addition to the economic impact of the war in Ukraine, we mustn’t forget the immediate social impact: there are still tens of thousands of educational migrants from Africa in Ukraine.

How are African Union (AU) states trying to address this situation? Do you see collective strategies?

This is where the continental organisation is currently reaching its limits: member states are divided. During the vote in the special session of the UN General Assembly 2 March 2022, on the condemnation of the Russian Federation’s war of aggression, 28 out of 55 AU member states voted in favour of the resolution; Eritrea voted against, 17 states abstained, and eight states preferred not to attend the session. Whatever the reasons in individual cases (a critical attitude towards “the West” not only for ideological reasons; old ties with the Soviet Union – which, however, also included Ukraine –; new dependencies of some states in the security sphere, etc.), the continent’s disunity on central geopolitical issues could hardly be documented more clearly.

The communitisation of policy areas has not yet reached the point where the AU Commission could speak for member states on this issue.

Since mid-2020, there have been a number of successful or attempted coups in several African countries. How are these attempted overthrows connected?

Indeed, all of this is taking place against the backdrop of ongoing political crises on the continent. The number of unconstitutional changes of government, or UCGs, has increased sharply in the past two or three years. In West Africa in particular, there have been a number of attempted but also successful coups d'état (such as Mali 2020 and 2021, Burkina Faso 2022, Guinea 2020). These coups are each caused by their own path dependencies, the long-standing and futile confrontation with violent extremism and terrorism (just think of the Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara, Boko Haram, etc.), and a dramatic decline in the belief in the legitimacy of often corrupt governments, as a result of which the actions of the military in turn gain public support. This also undermines the role of France or the EU in the region.

Although the African Union and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) are taking decisive action against the rebels, including suspending them from participation in their organisations, the sanctions are currently coming to nothing. In most cases, a return to constitutional order is difficult to imagine in the foreseeable future.

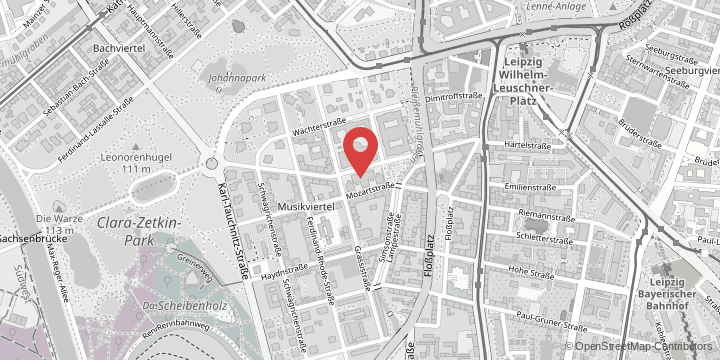

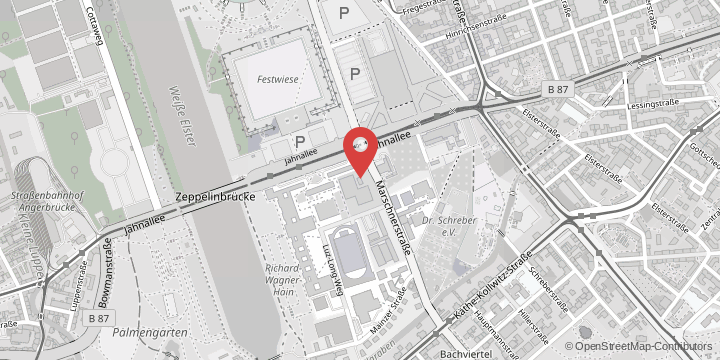

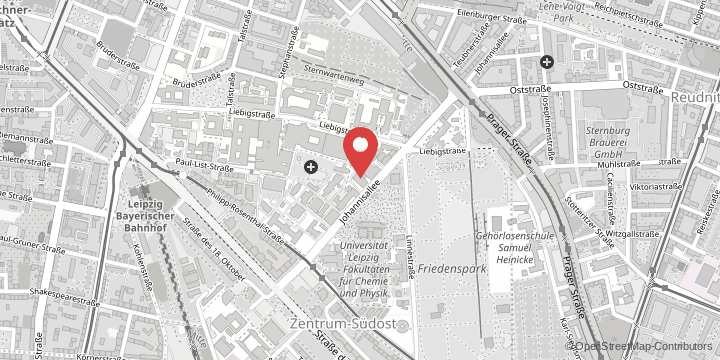

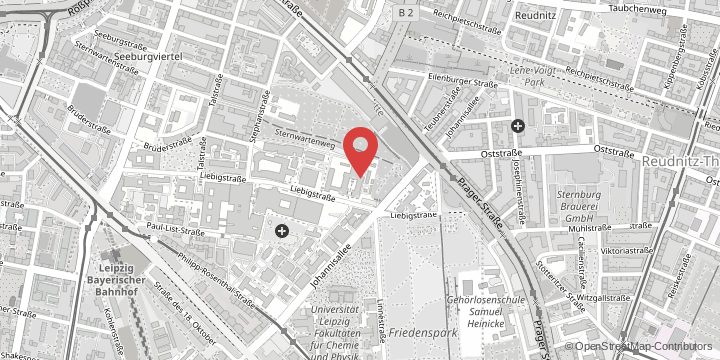

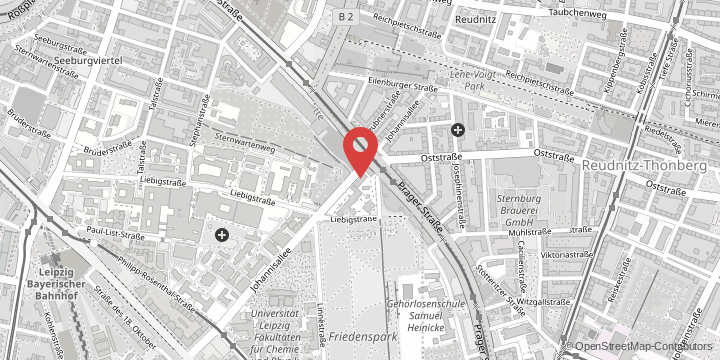

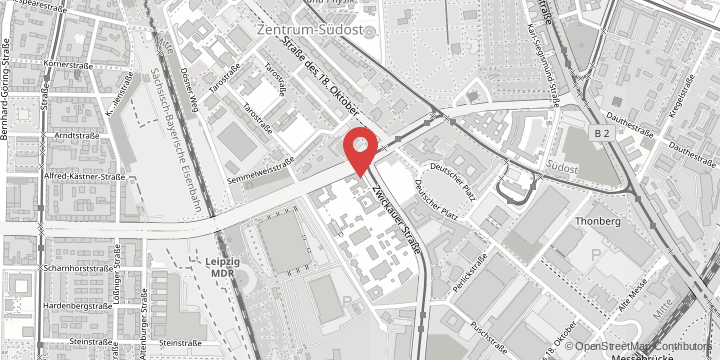

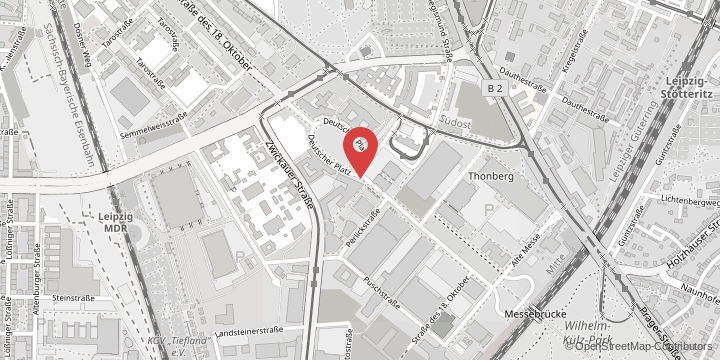

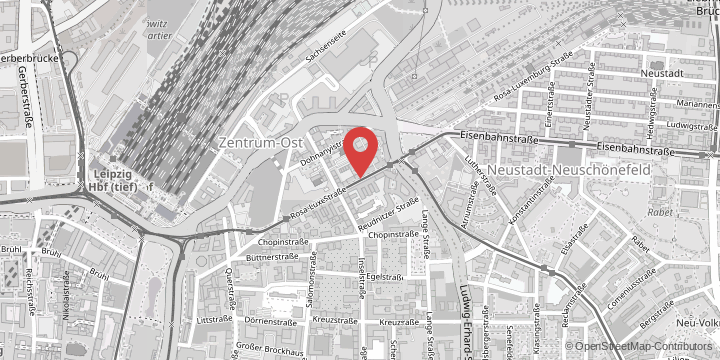

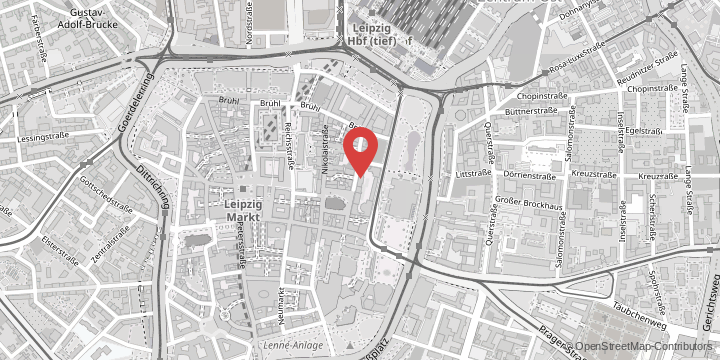

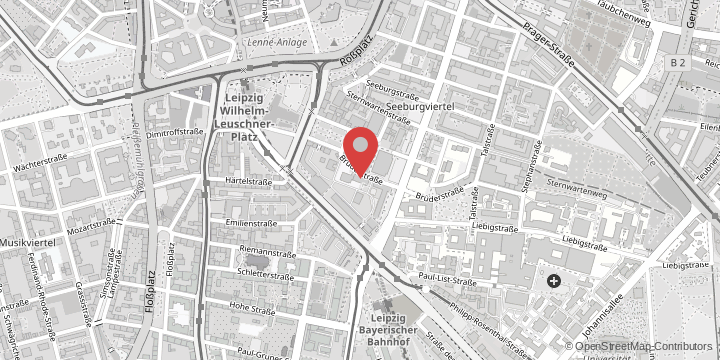

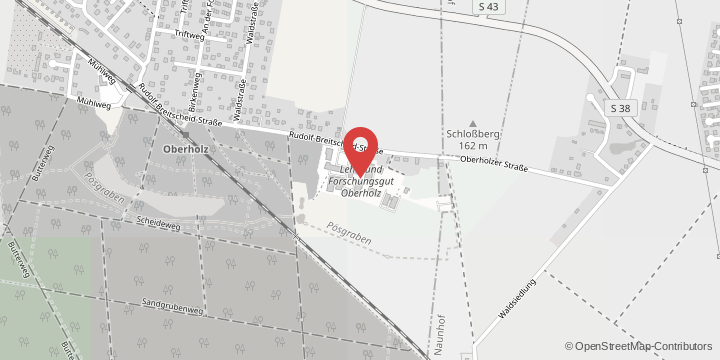

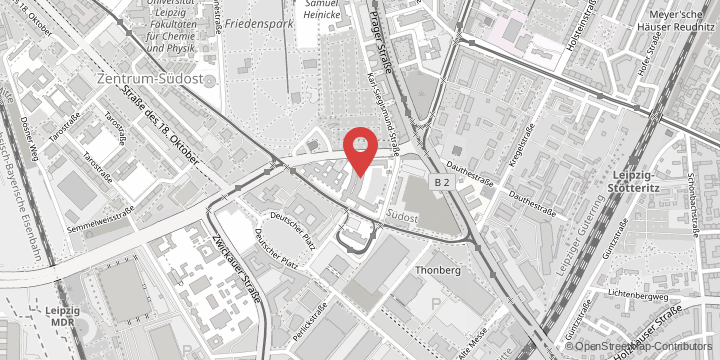

It is this latter topic that will be the focus of a round table at the annual conference on 28 April 2022. The organisers of the round table, who just launched the BMBF-funded network project “African Non-Military Conflict Intervention Practices” this month, will discuss these issues with Ambassador Said Djinnit, the first AU Commissioner for Peace and Security (2003–2008) and long-time Special Representative and Head of the United Nations Office for West Africa (2008–2014) and Special Envoy of the United Nations for the Great Lakes region (2014–2019).

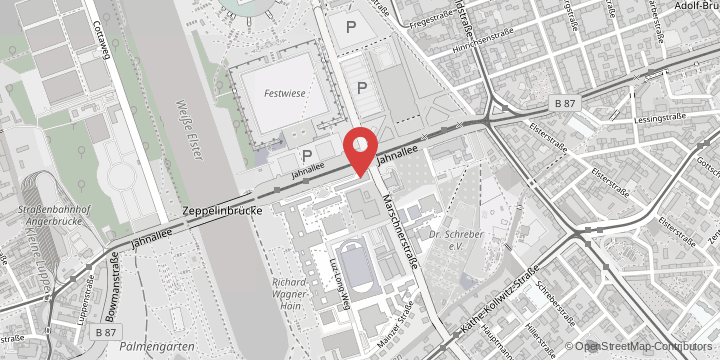

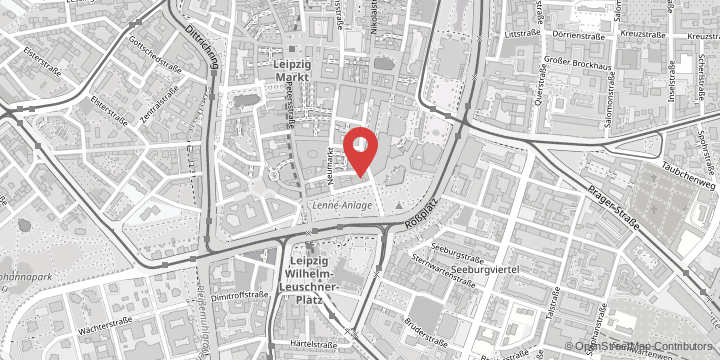

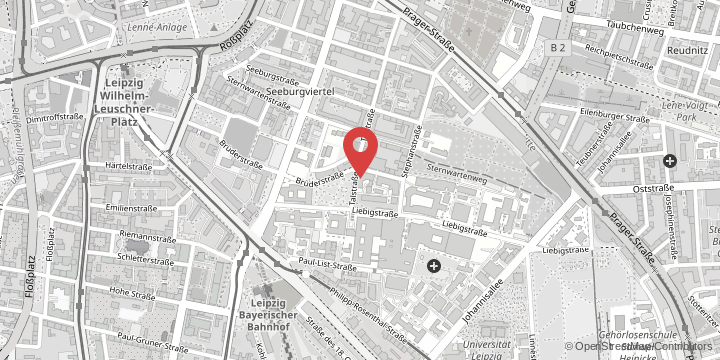

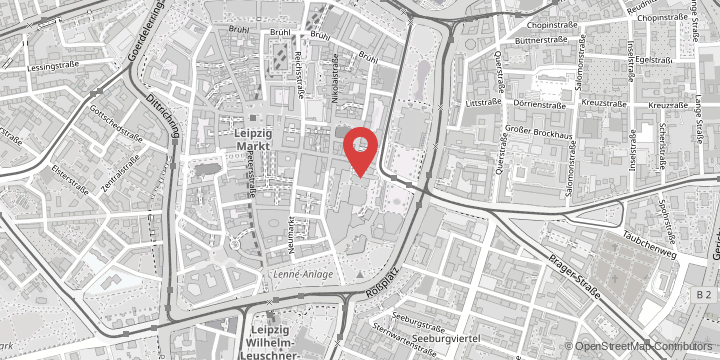

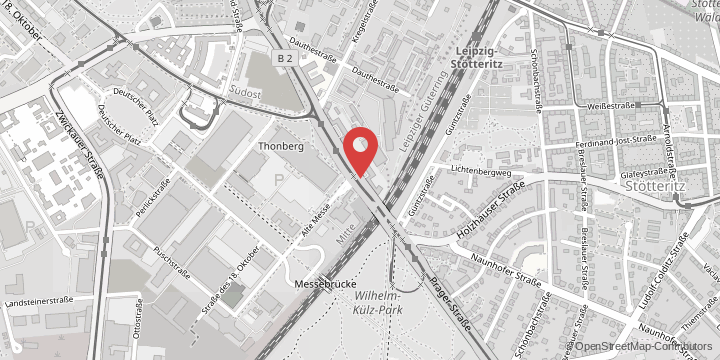

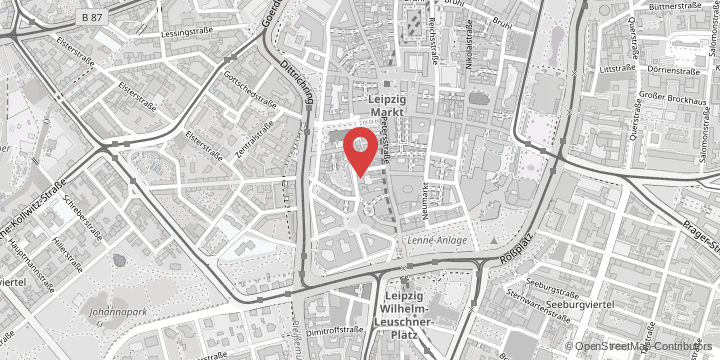

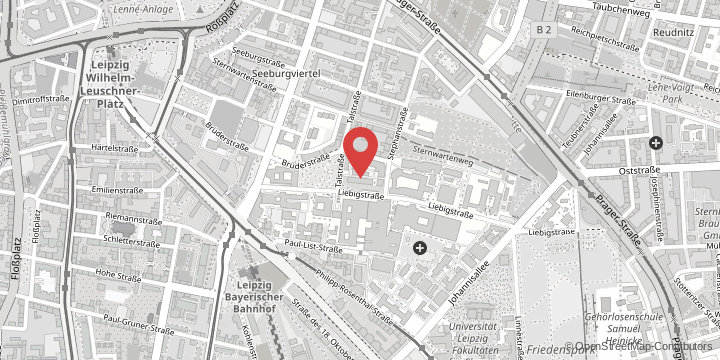

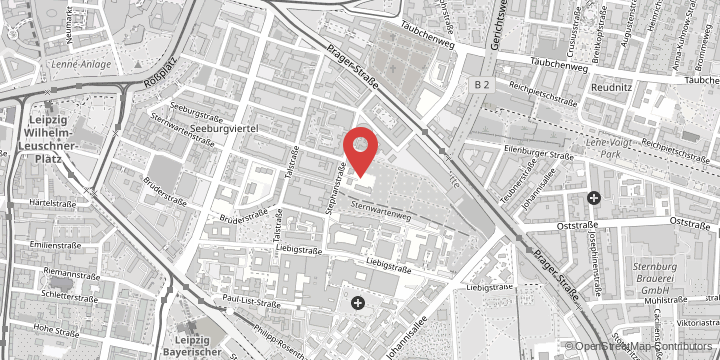

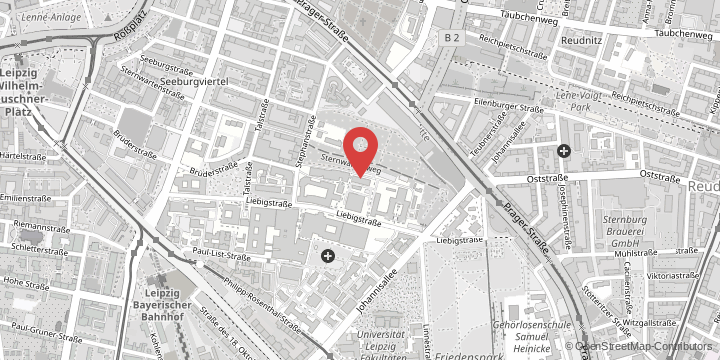

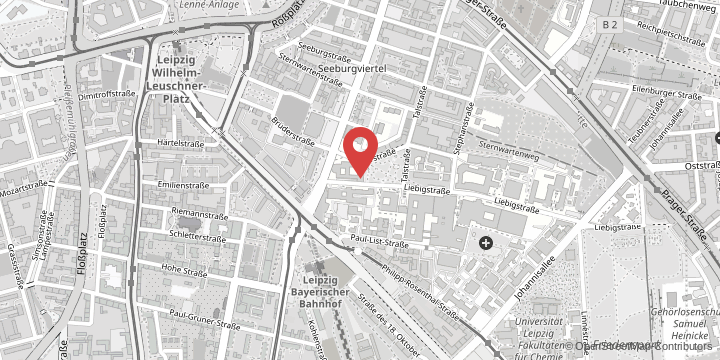

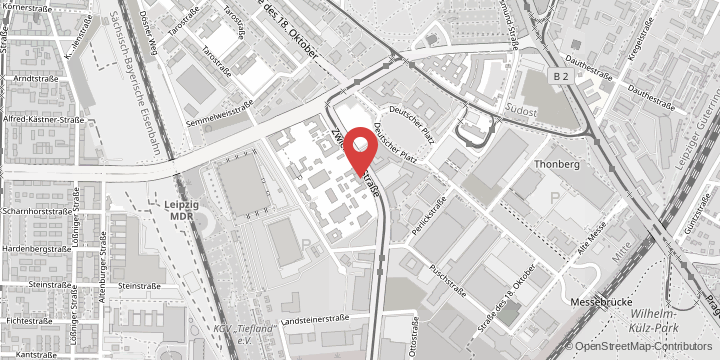

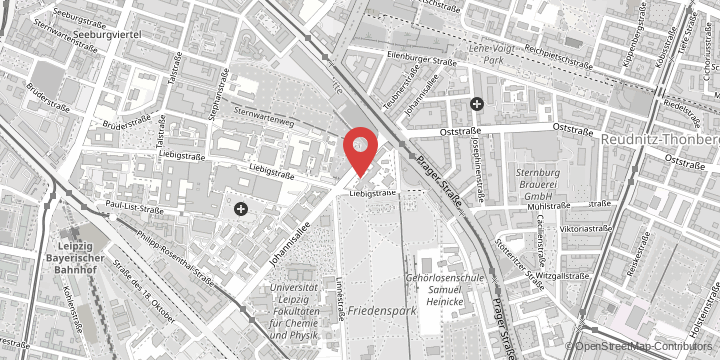

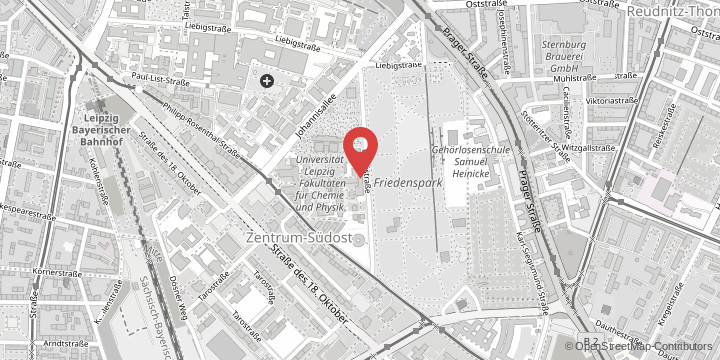

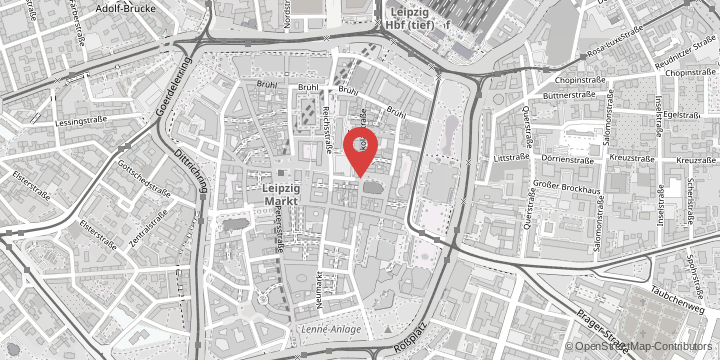

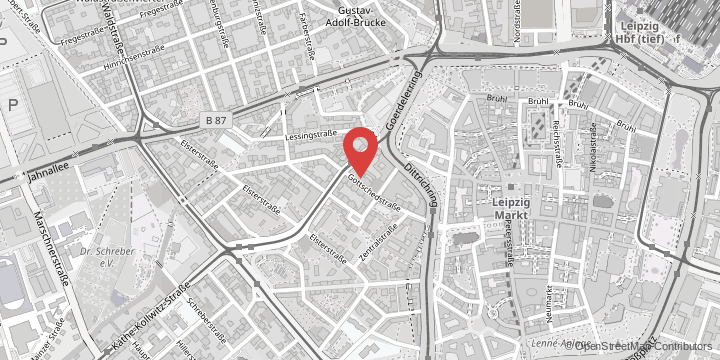

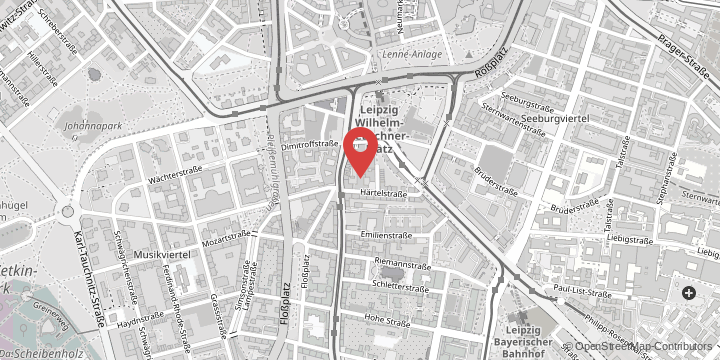

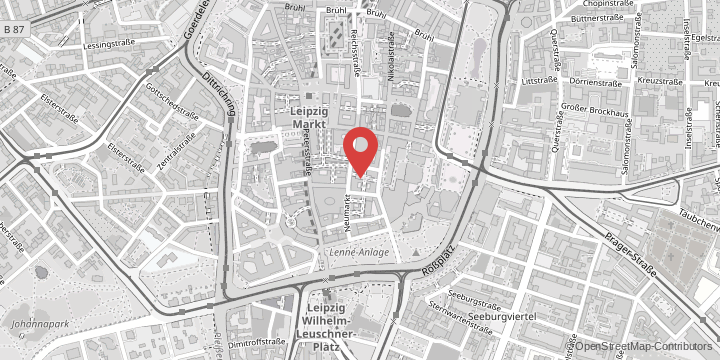

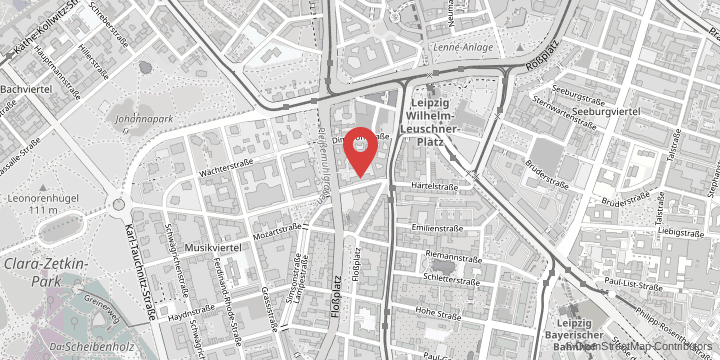

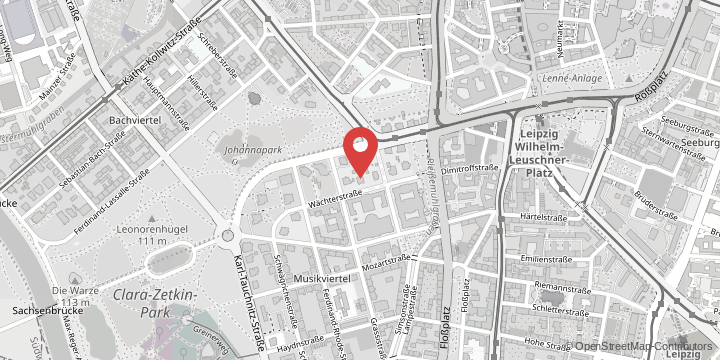

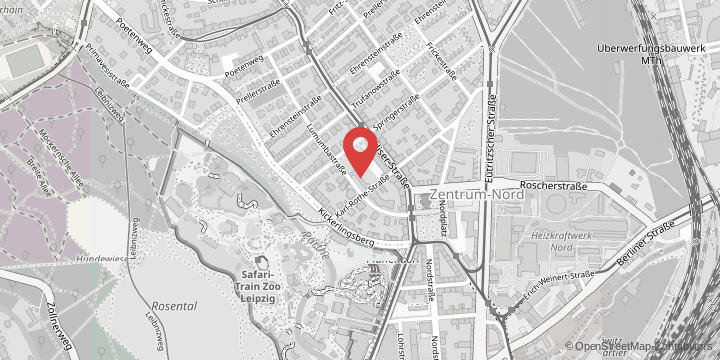

ReCentGlobe annual conference:

In 14 themed panels at ReCentGlobe’s annual conference, researchers will look at the mounting crises in different regions of the world, which raise the question of whether the framework for social transformations is fundamentally shifting: has globalisation, as it has become the focus of attention since the late 1980s, come to its end? Are we seeing a retreat from the goal of increasingly dense global interdependencies? Or are the global challenges becoming more urgent and calling even more strongly than in the past for answers that must be found together internationally?

These are questions that the Leipzig Research Centre Global Dynamics (ReCentGlobe) is addressing and making the focus of its upcoming annual conference. In order to find answers, historical experience is mobilised and the comparative view directed at different world regions, in which the caesura in the global framework conditions is having an impact in very different ways. But these differences cannot obscure the fact that war in Ukraine and hunger in parts of Africa are as interrelated as the transformation of the Amazon is to the future of island nations in the Pacific.