According to the study, only 2 per cent of people in eastern Germany still have a narrow, extremely right-wing world view. In 2020, this figure was still around 10 per cent. “Agreement with extreme right-wing statements is not only decreasing in the whole of Germany, but especially in eastern Germany. That’s good news, but it’s only half the picture,” says head of the study Professor Oliver Decker. “While elements of neo-Nazi ideology are rarer, resentment of those perceived as ‘different’ has actually increased,” adds co-head Elmar Brähler. According to the study, the percentage of people with “manifestly xenophobic” attitudes in eastern Germany has risen from 27.8 to 31 per cent compared to 2020, whereas it has fallen from 13.7 to 12.6 per cent in western Germany. Forty per cent of eastern Germans say they believe Germany is being “swamped with foreigners”, and 23 per cent of western Germans also agree with this statement.

The percentage of people who are satisfied with constitutional democracy rises from 65 per cent to 90 per cent in eastern Germany; nationwide, it is approved of by 82 per cent of people. “Compared with authoritarian systems, democracy as a form of government is becoming more popular,” comments Oliver Decker. But: only just half of respondents expressed their approval of everyday democratic practice. Despite the high level of satisfaction with the form of government, there is evidently a widespread feeling of not having any political influence.

The two researchers see this as fitting into the crisis situation during the pandemic and the current war: the executive branch is strengthened and its actions are widely supported, but this authoritarian security comes at a price. Though people accept their feelings of powerlessness and the restrictions on their own lives, this also leads to an increase in aggression. “That is why neo-Nazi ideology, and with it elements of extreme right-wing attitudes, are less important at present. But now other anti-democratic motives are coming to the fore,” explains Professor Elmar Brähler, “they are prejudices, hatred of ‘others’, and this is not less common and is served just as well by far-right parties.”

For example, opposition to Muslims has increased in eastern Germany compared to 2020, with 46.6 per cent agreeing with the statement that Muslims should be banned from immigrating to Germany, compared to 23.6 per cent in western Germany. Sinti and Roma are also disapproved of by 54.9 per cent of eastern Germans and 23.6 per cent of western Germans. Meanwhile, “guilt-deflecting anti-Semitism” remains the most widespread expression of anti-Semitism across Germany, with just under half of respondents agreeing with corresponding statements. Support for anti-feminist statements has also increased since 2020. Twenty-seven per cent of respondents believed that women “who demand too much shouldn’t be surprised if they’re put back in their place”.

“The simultaneous rise in anti-feminism, guilt-deflecting anti-Semitism and also hatred of Muslims, Sinti and Roma, indicates a shift in the motives of anti-democratic attitudes, not a strengthening of democracy,” says Professor Oliver Decker. “Besides xenophobia, right-wing extremists today have many more opportunities to find a foothold in mainstream society, not fewer.”

In addition, society is still polarised by the pandemic. It is true that one positive development is that the proportion of respondents with a tendency to believe in conspiracy theories has declined significantly since 2020, from 38.4 per cent in 2020 to 25 per cent in 2022. “Due in no small part to the internet, political discourse is dominated by two groups: an entrenched group of 13 per cent who oppose vaccination versus 19 per cent who strongly resent those who oppose vaccination,” says Professor Oliver Decker. “In both groups, resentment not only of each other, but also of many ‘others’ is equally strong.”

Decker and Brähler observe a similar fragmentation of society to some extent in respondents’ reactions to the Ukraine war. Although no one explicitly supported the war, the supporters of arms deliveries to Ukraine on the one hand and those who sympathise with Russia on the other also share a generally higher propensity for authoritarian aggression. “Here, too, it can be seen that the authoritarian mobilisation potential still exists, but it can currently be satisfied with socially conformist goals,” says Professor Elmar Brähler.

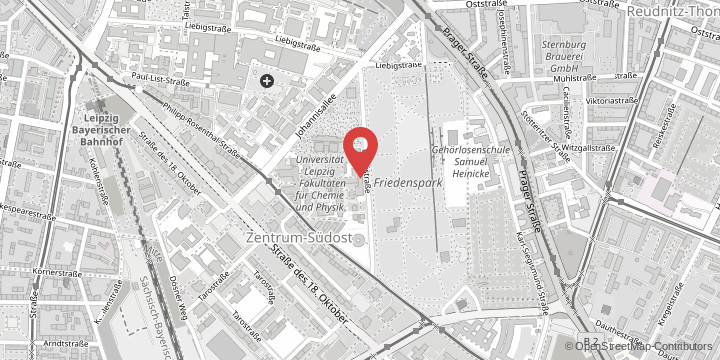

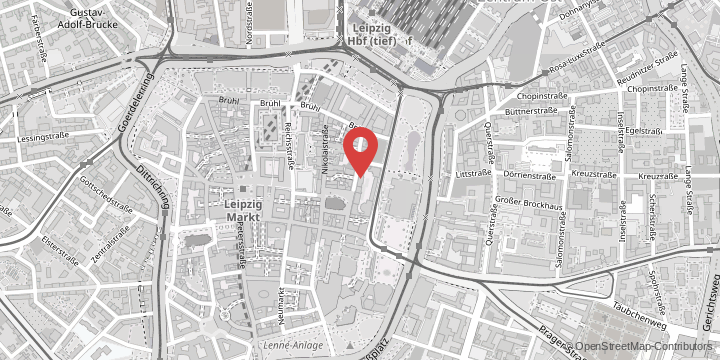

About the Leipzig Authoritarianism Study

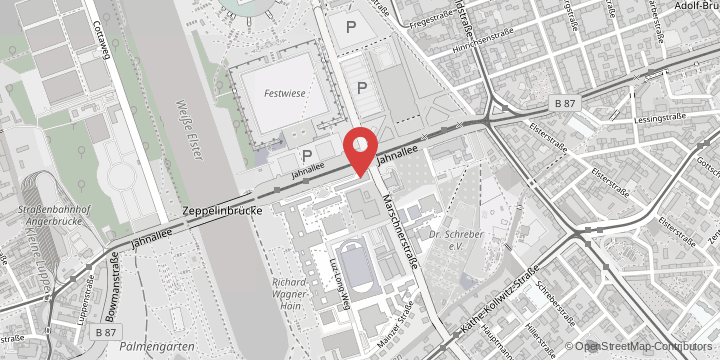

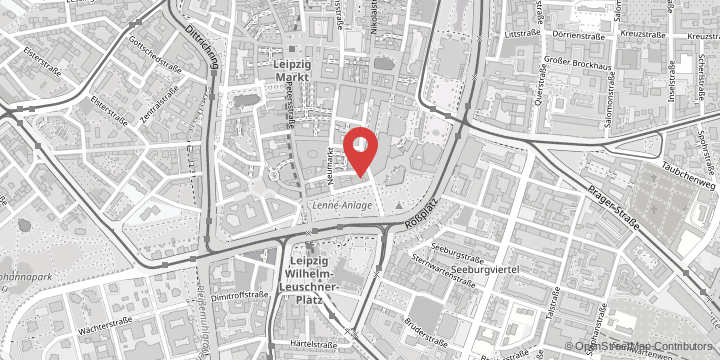

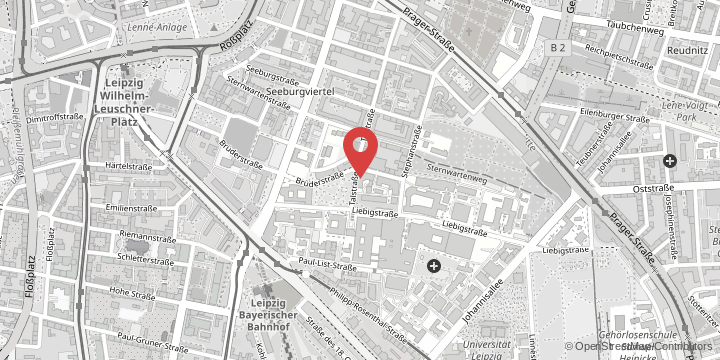

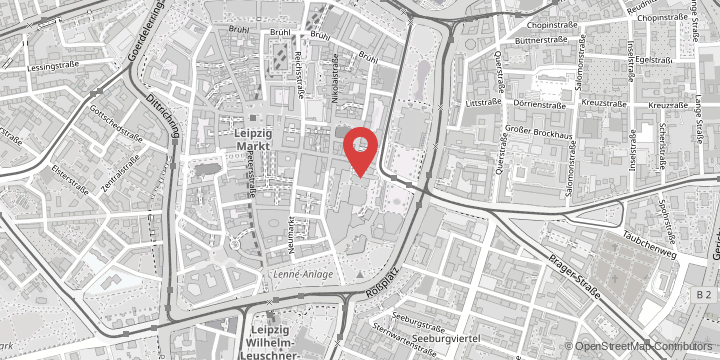

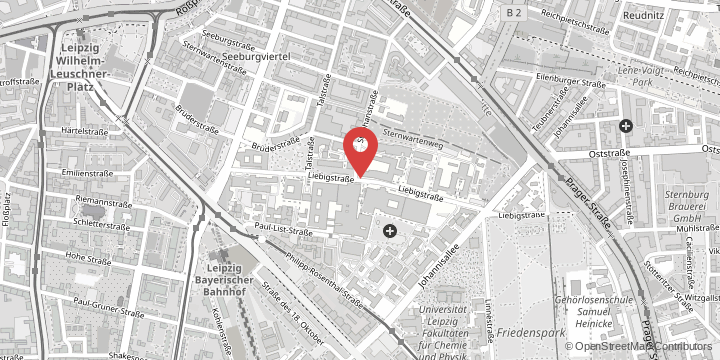

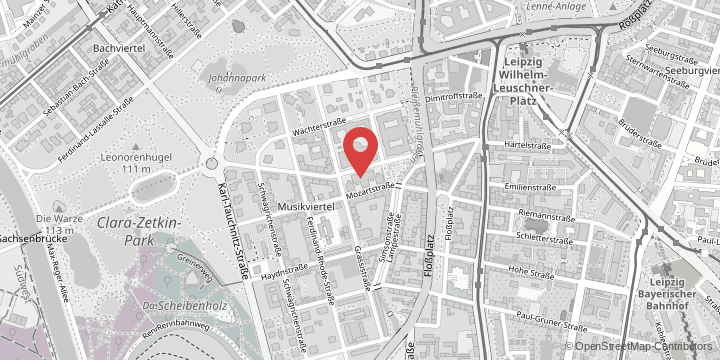

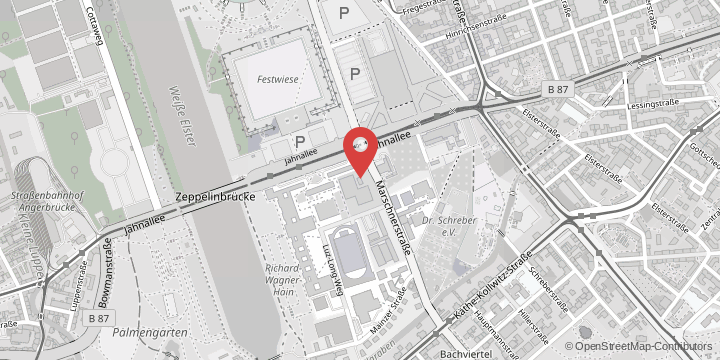

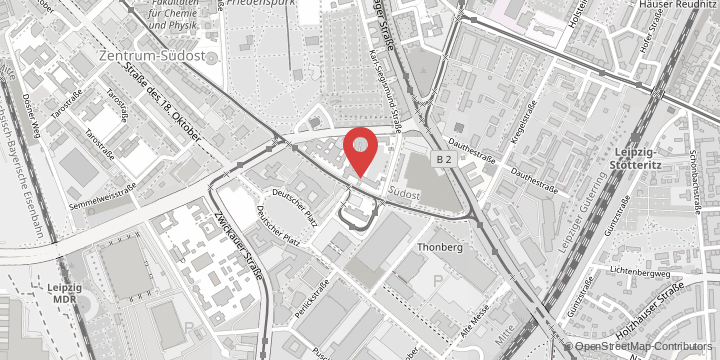

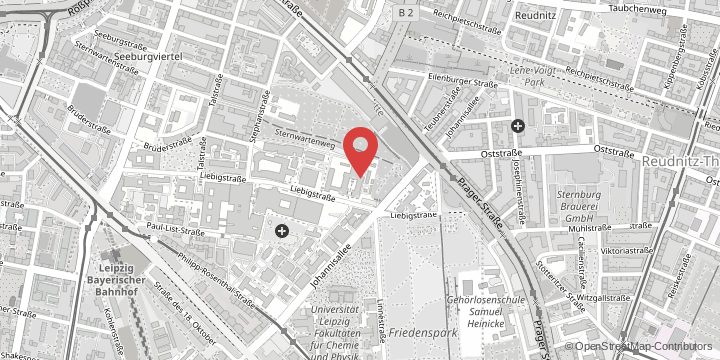

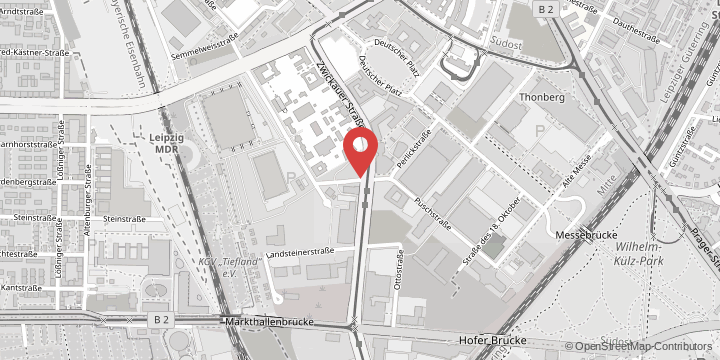

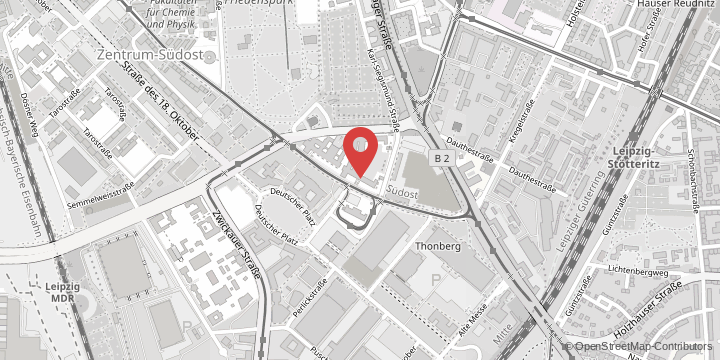

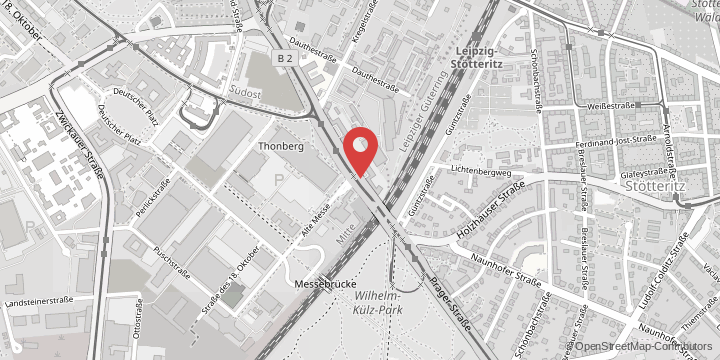

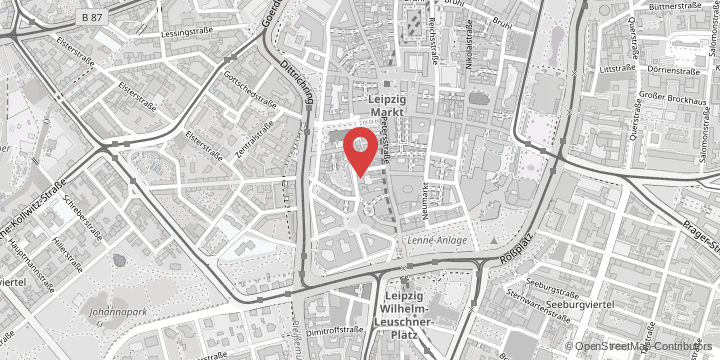

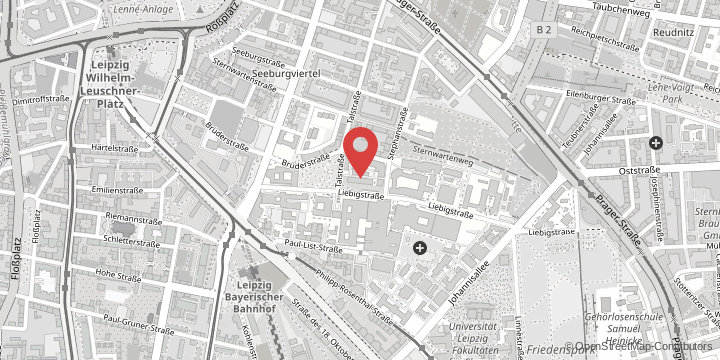

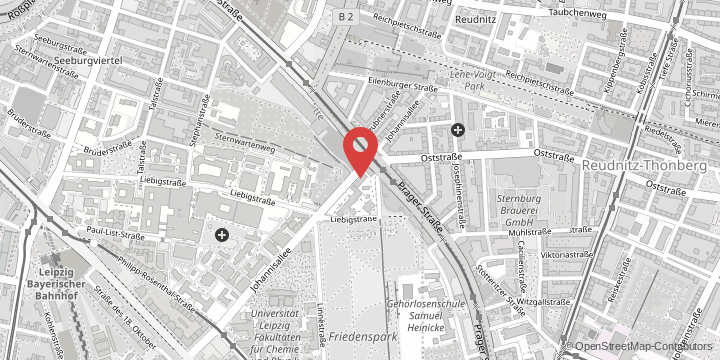

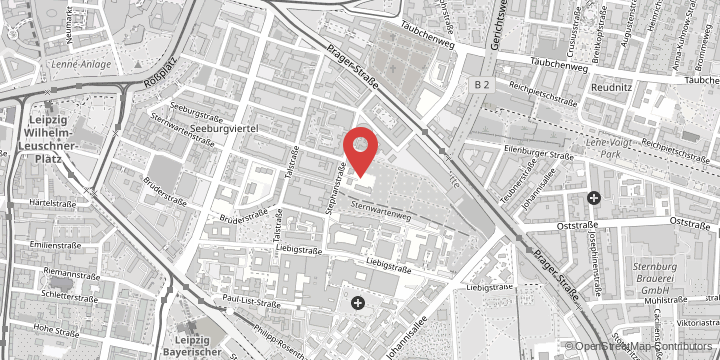

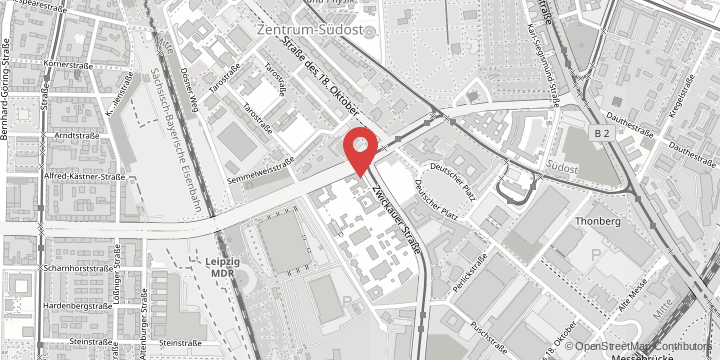

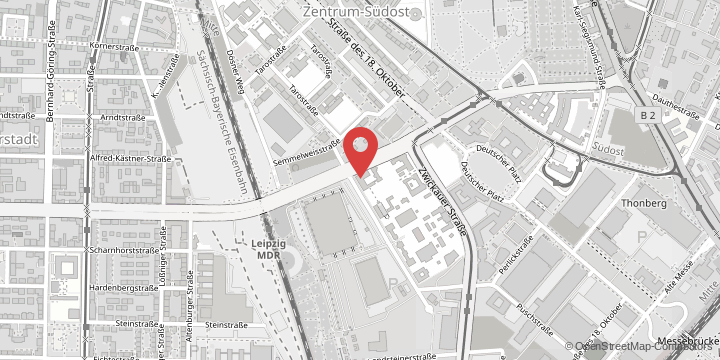

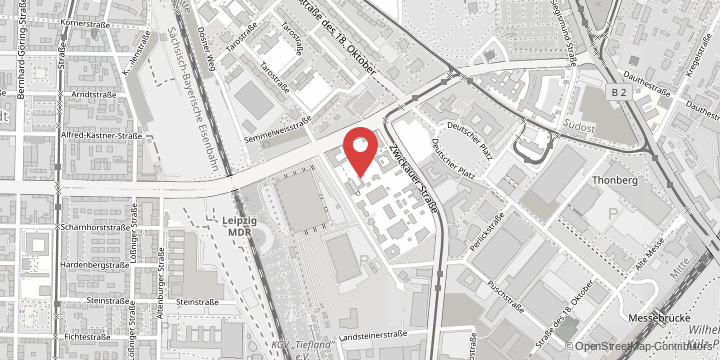

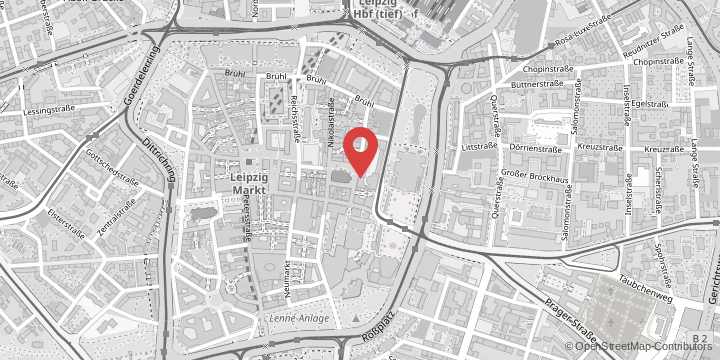

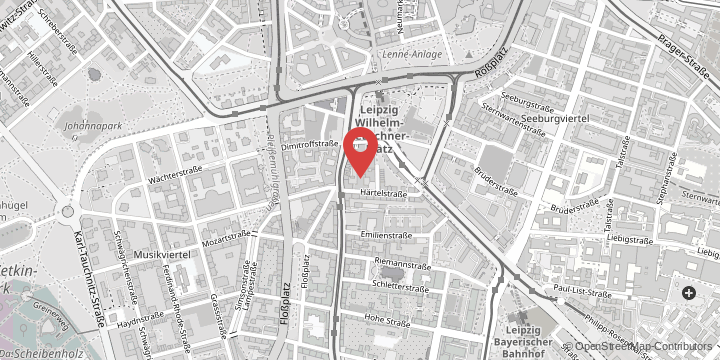

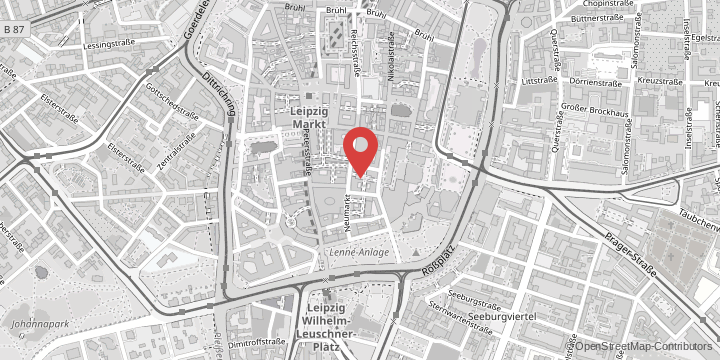

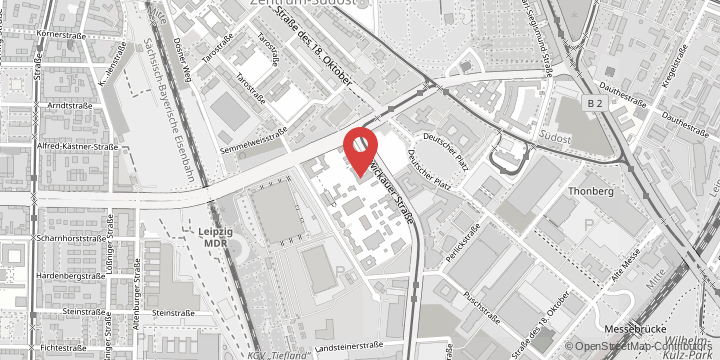

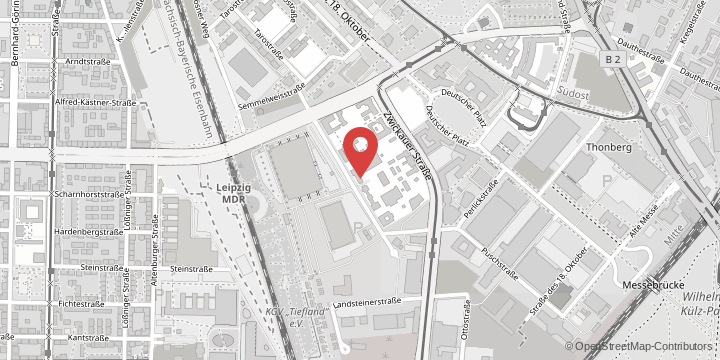

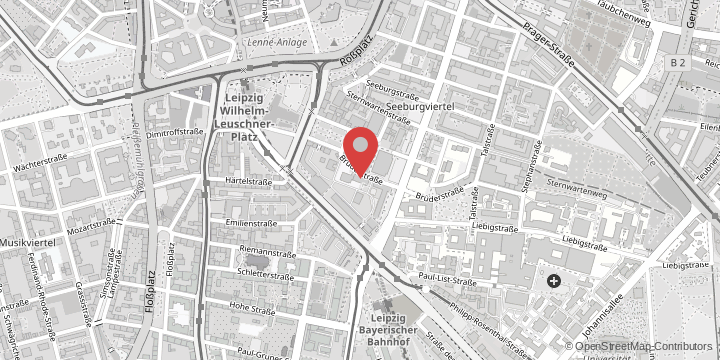

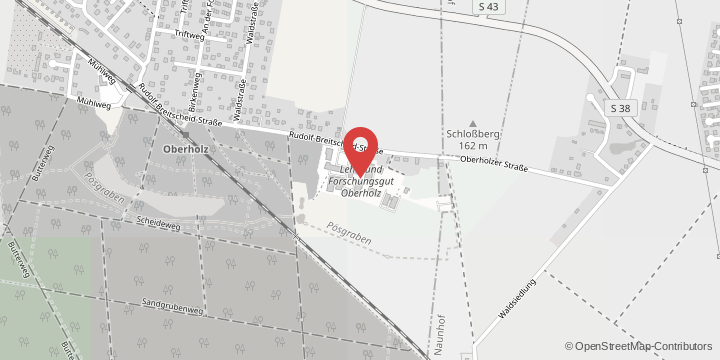

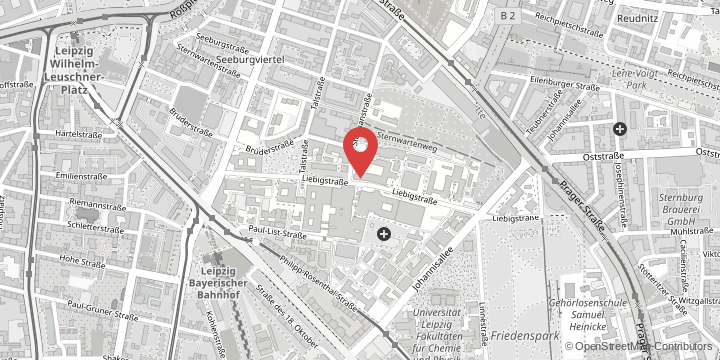

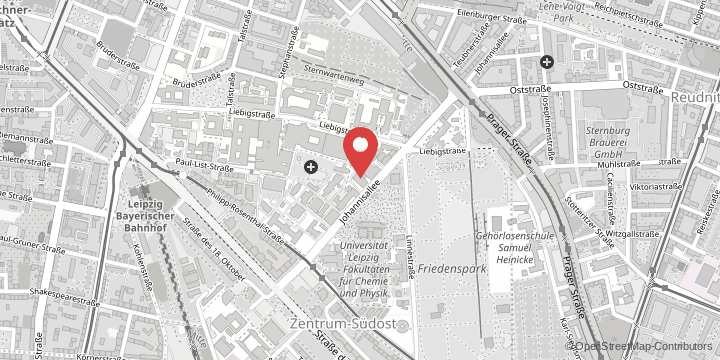

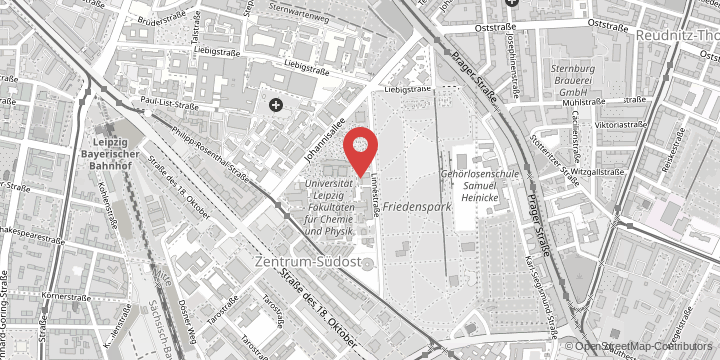

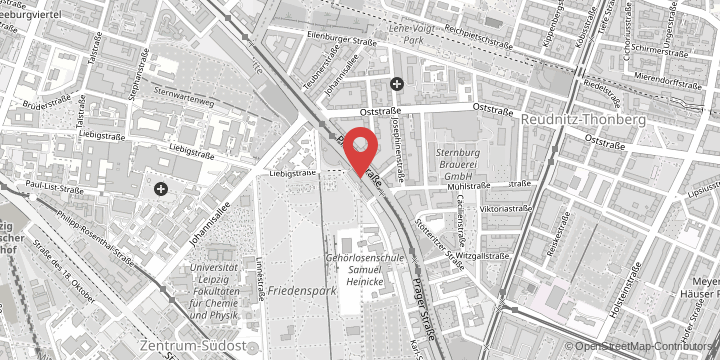

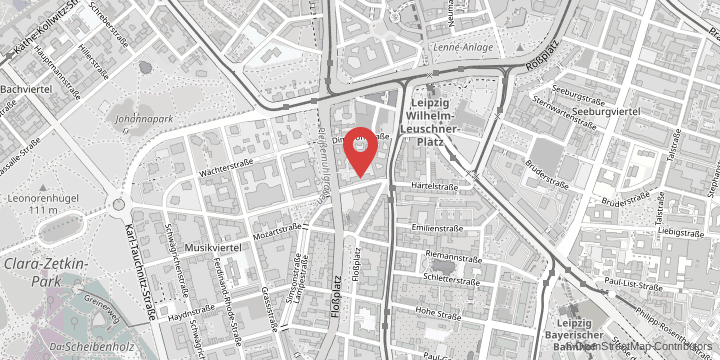

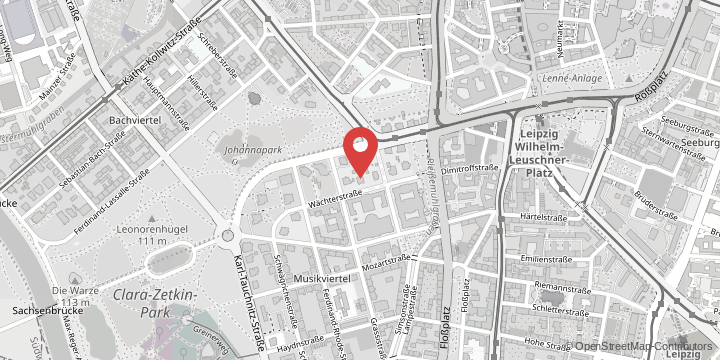

The two researchers at Leipzig University have been observing changes in authoritarian and far-right attitudes in Germany since 2002. From 2006 until 2012, the so-called “Mitte” Studies were carried out in cooperation with the Friedrich Ebert Foundation. Since 2016 the Leipzig studies have been published in cooperation with the Heinrich Böll Foundation and the Otto Brenner Foundation.

In the eleventh wave, the opinion research institute USUMA surveyed 2522 people nationwide between early March and the end of May 2022 on behalf of Leipzig University using a paper-and-pencil method. In order to be able to analyse attitudes towards the war in Ukraine, an online survey with 4000 respondents was commissioned from the polling institute Bilendi & respondi after the start of the representative study.

All of the results from this new authoritarianism study have now been published in the book Autoritäre Dynamiken in unsicheren Zeiten. Neue Herausforderungen – alte Reaktionen?, which is available from Psychosozial-Verlag.