With the ERC Starting Grant “Forest Vulnerability to Compound Extremes and Disturbances in a Changing Climate” (ForExD), a highly funded five-year grant from the European Research Council (ERC), you are investigating how vulnerable forests are to extreme events and disturbances in the context of climate change. The damage to forests in central Germany has been highly visible. What exactly are you investigating here and what have you discovered so far?

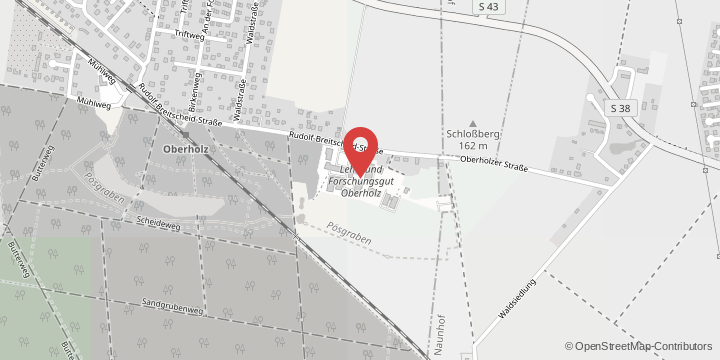

The ForExD project aims to better understand how weather and climate extremes are linked to forest disturbances such as fires, insect outbreaks or drought-related tree mortality. Over the past decade or two, we have seen many surprising disturbance events linked to weather extremes, such as megafires from Australia to Alaska, or the widespread tree mortality in Central Europe following the summer drought in 2018. I am interested in three questions: how has climate change contributed to these events, why are some forests more vulnerable to extremes than others, and what does this mean for climate change mitigation? For example, in the case of tree mortality in Central Europe, and therefore also in central Germany, we have shown that this was not just due to the drought of 2018, but the cumulative effect of three consecutive hot and dry summers from 2018 to 2020, which reinforced each other’s effects. In some countries, such as the Czech Republic, these effects have caused forests to release carbon into the atmosphere instead of absorbing it. This is worrying because many climate change mitigation measures depend heavily on forests.

What do you think is the role of climate extremes in changing the dynamics of the carbon cycle, and how can we better prepare for them?

Currently, forests absorb almost 25 per cent of human-made CO2 emissions. But we also see that weather and climate extremes can lead to large carbon losses, which in some cases are not immediately compensated by subsequent regeneration. In the light of recent extreme events, there are strong indications that the storage of further carbon in forests may soon be threatened by increasing disturbance events. However, we are not yet able to model these complex interactions, which means that there may be a feedback to climate change that is not yet fully captured in our projections.

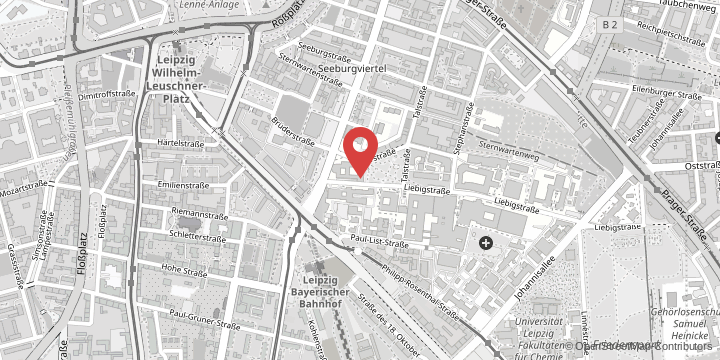

What are your plans for research and teaching at Leipzig University? What existing networks and projects will you be involved in?

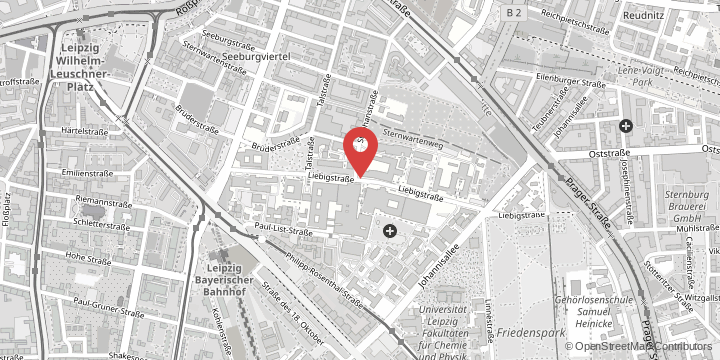

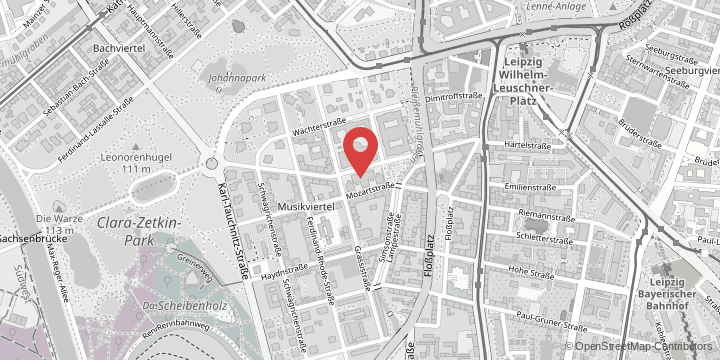

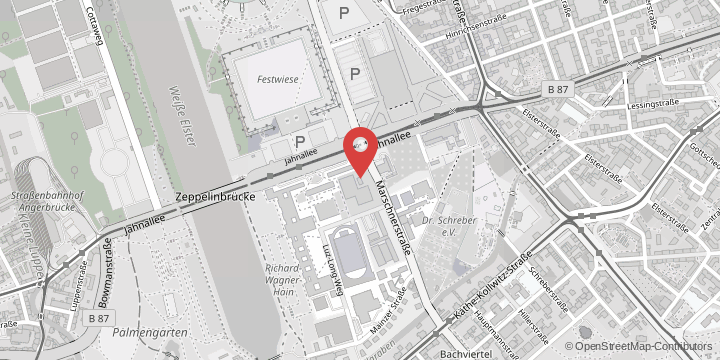

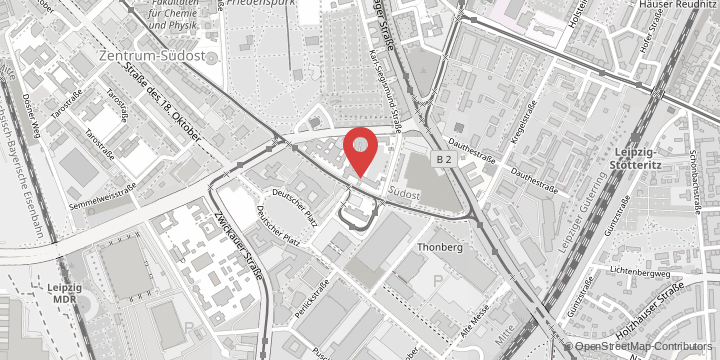

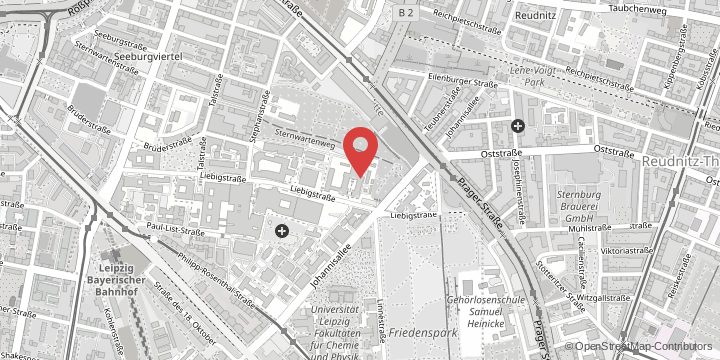

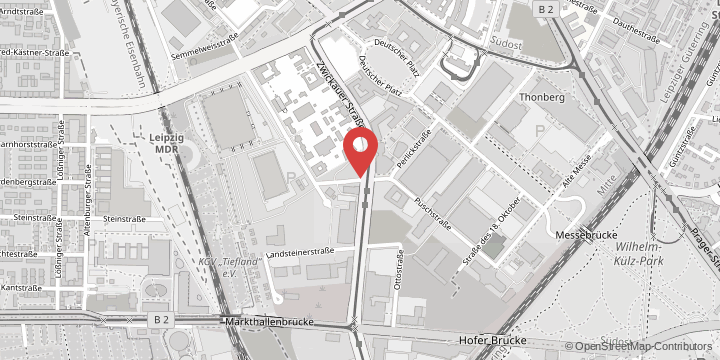

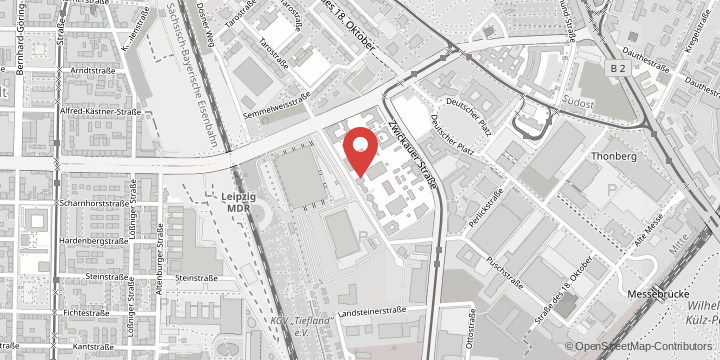

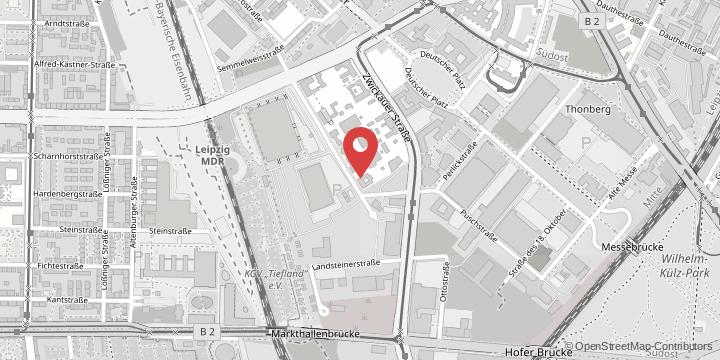

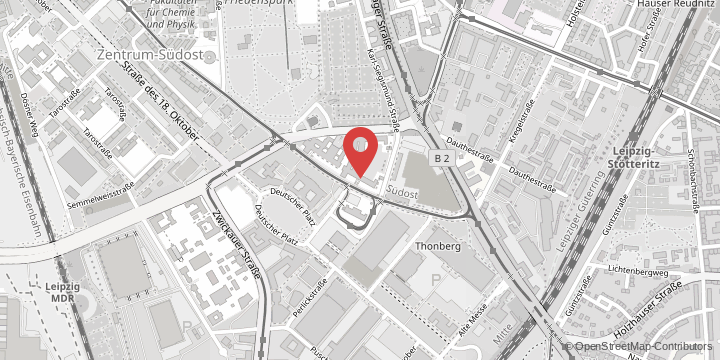

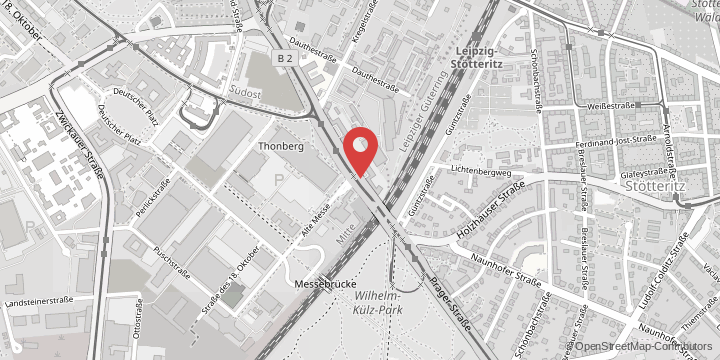

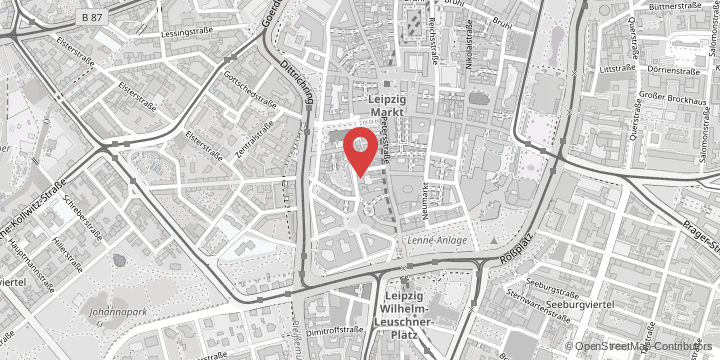

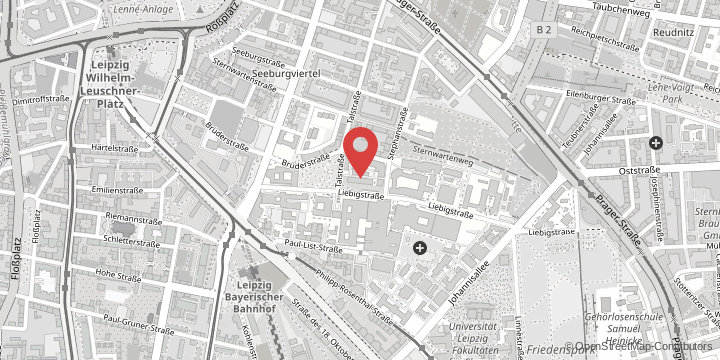

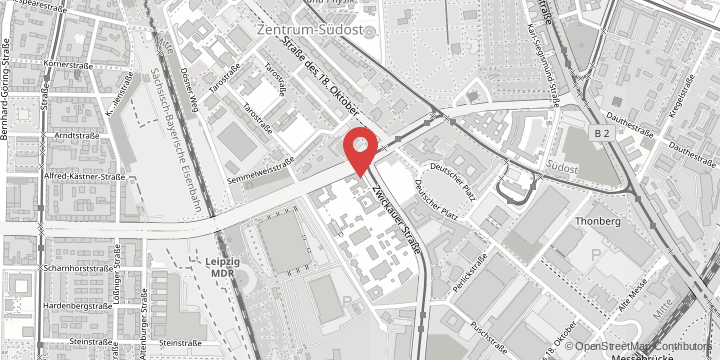

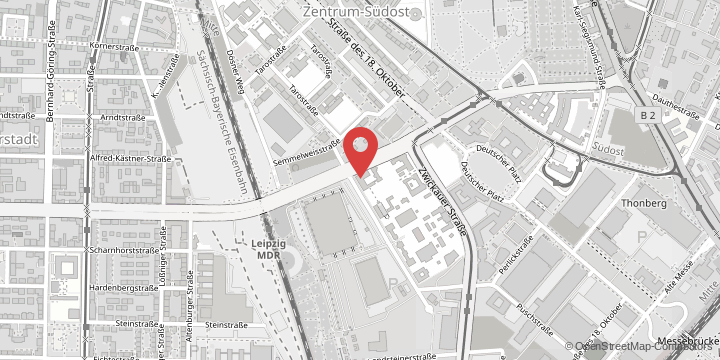

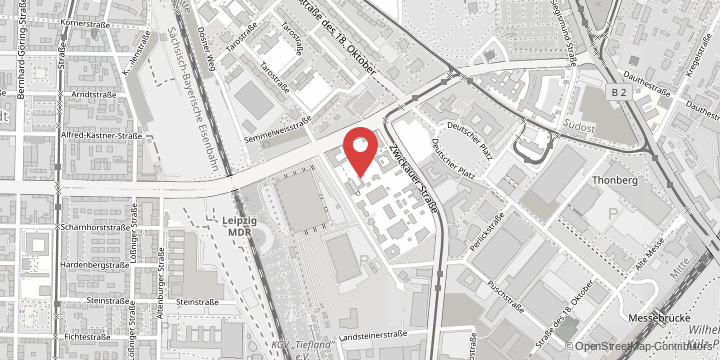

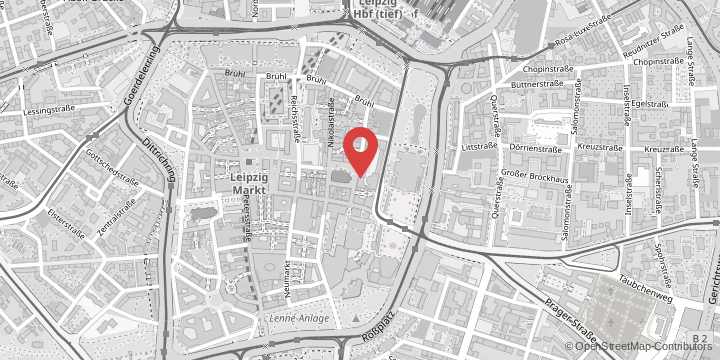

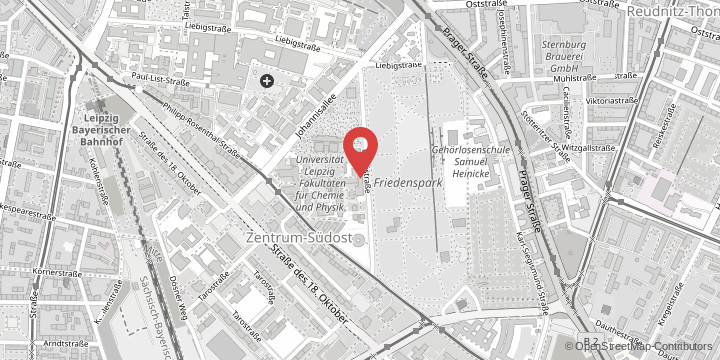

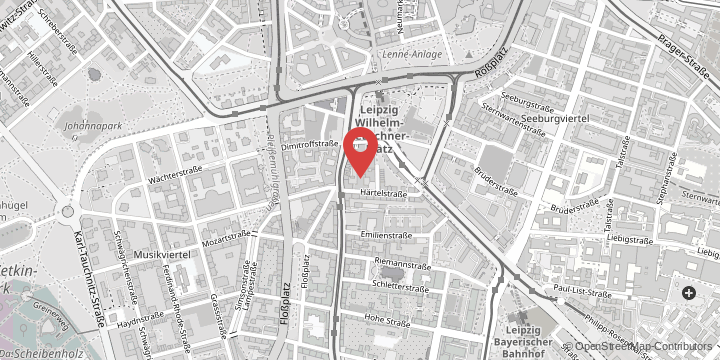

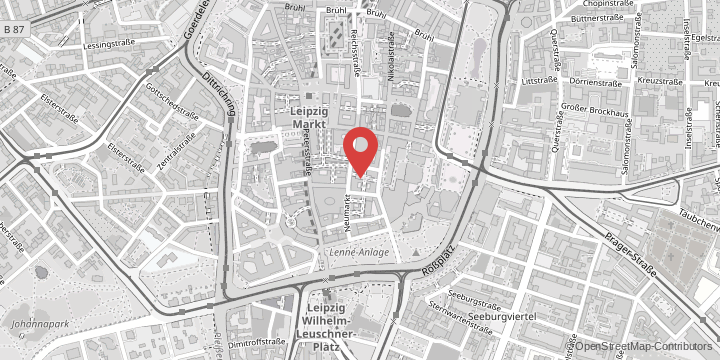

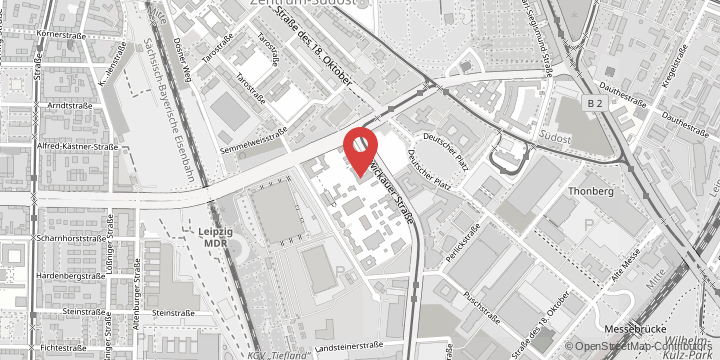

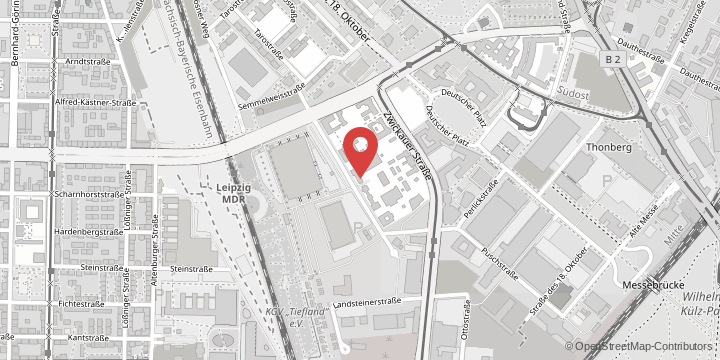

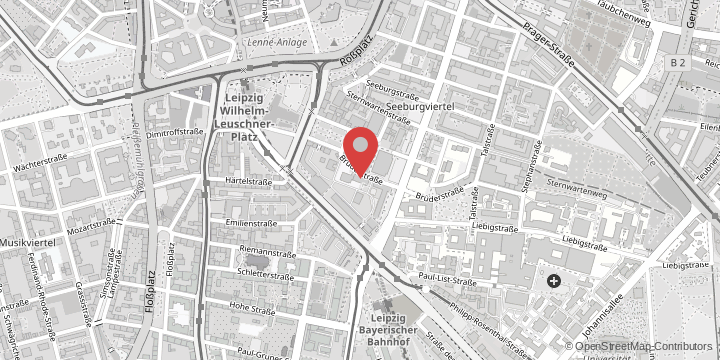

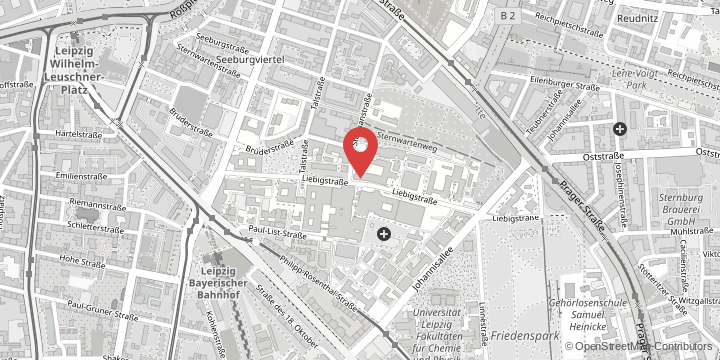

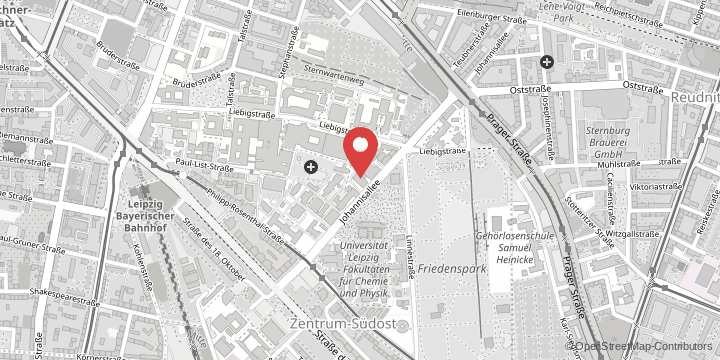

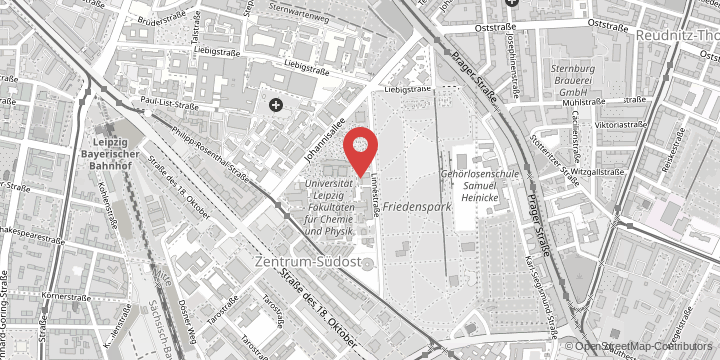

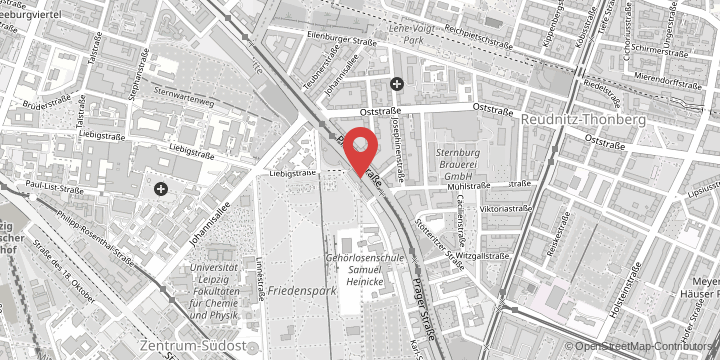

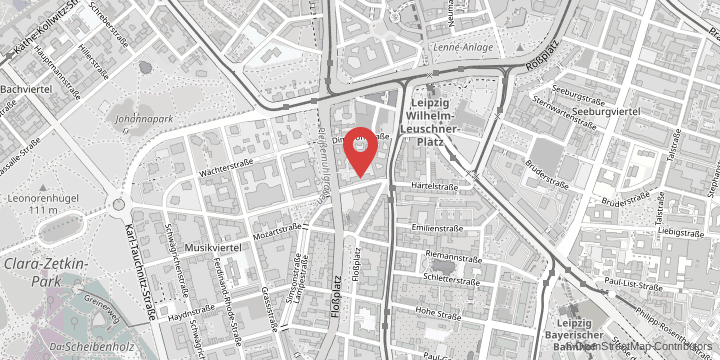

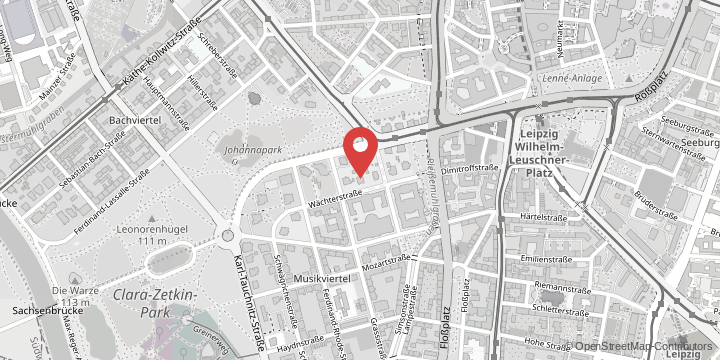

At Leipzig University, I am interested in developing my work at the interface of climate science and ecology. Vegetation regulates the exchange of energy, water and carbon between land and atmosphere and thus contributes to the regulation of the climate system. At the same time, it is itself influenced by the climate. My goal at Leipzig University is to continue researching these bidirectional interactions and, in particular, to inspire the next generation of scientists through my teaching on these topics. For example, an exciting proposal for a Collaborative Research Centre called Biodiversity Buffers for Climate Extremes, which we have just defended, aims to understand how biodiversity could help make ecosystems more resilient to weather and climate extremes, or even mitigate the events themselves. One challenge is that such studies need to bring together scientists from many different disciplines. In our Breathing Nature Cluster of Excellence project, this is even more complex, as we are also collaborating with various fields from the social sciences. Leipzig University is in a unique position to achieve this because of its highly visible, strong profile in Earth system research, focusing on the atmosphere, the biosphere and their interactions. I am happy to be part of these exciting developments and to now be able to help shape the Institute for Earth System Science and Remote Sensing, and especially to take the students along on this journey.