In recent years, researchers from across disciplines have identified striking and seemingly universal relationships between the size of cities and their socioeconomic activity. Cities create more interconnectivity, wealth, and inventions per resident as they grow larger. However, what may be true for city populations on average, may not hold for the individual resident.

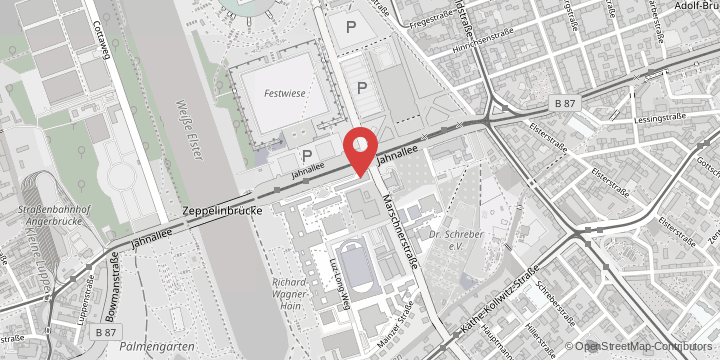

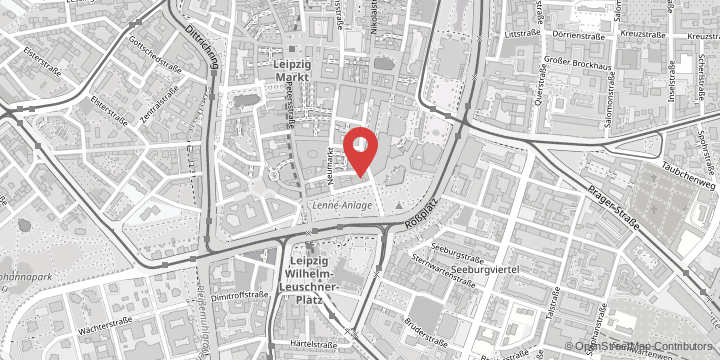

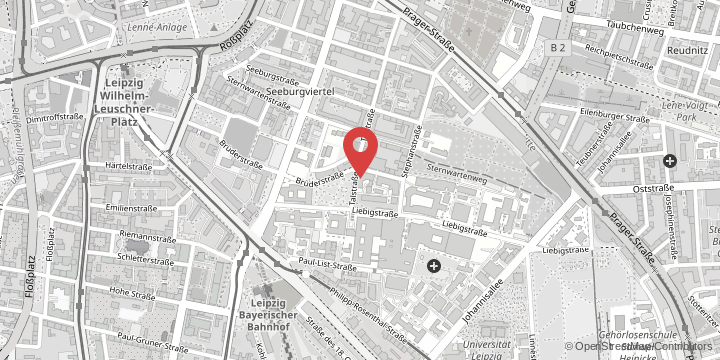

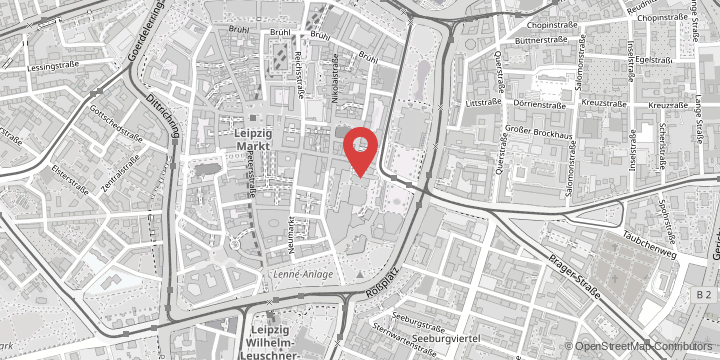

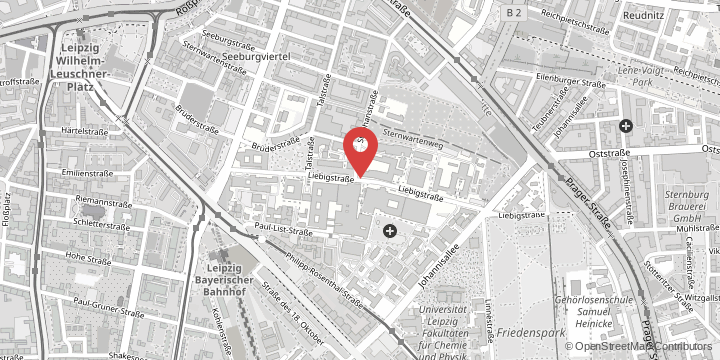

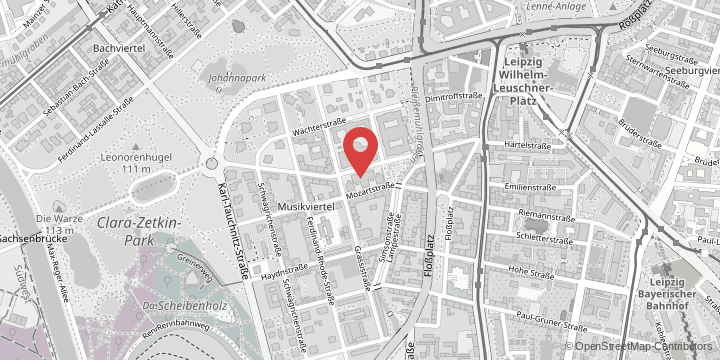

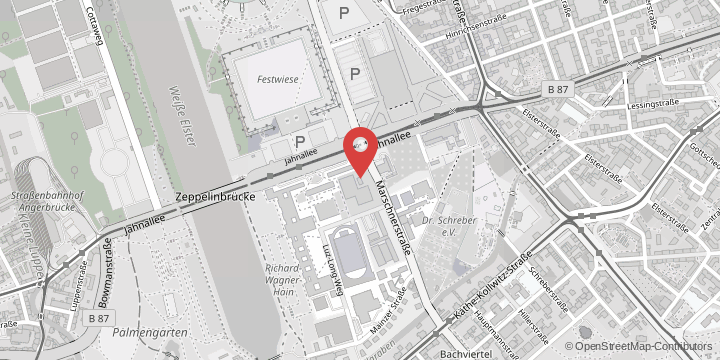

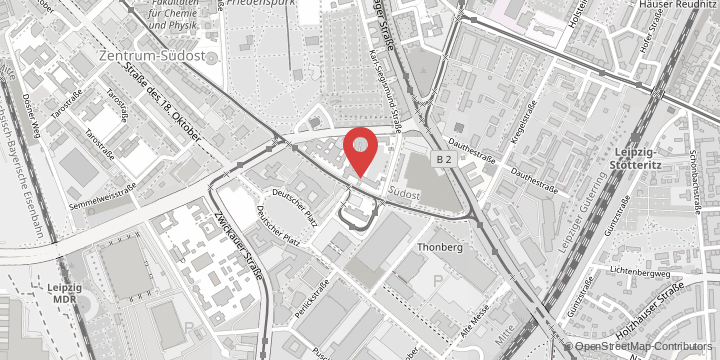

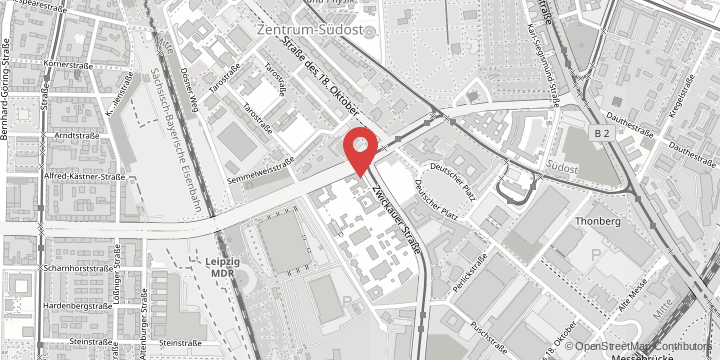

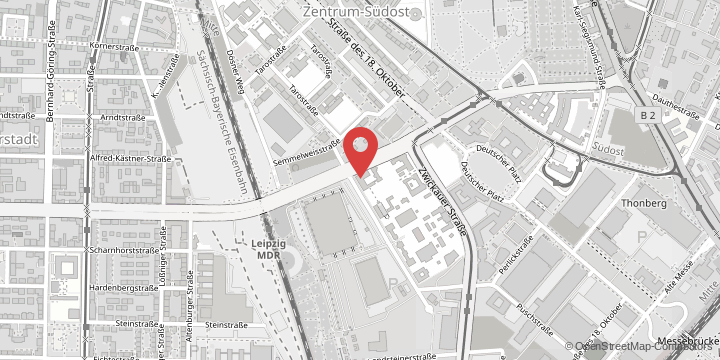

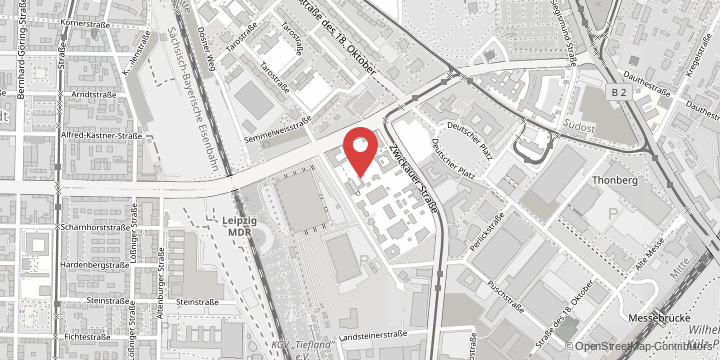

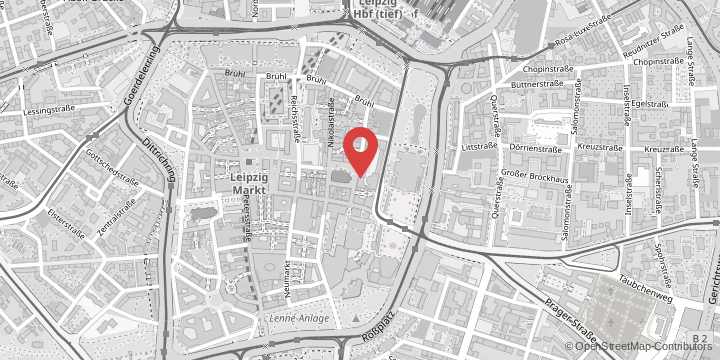

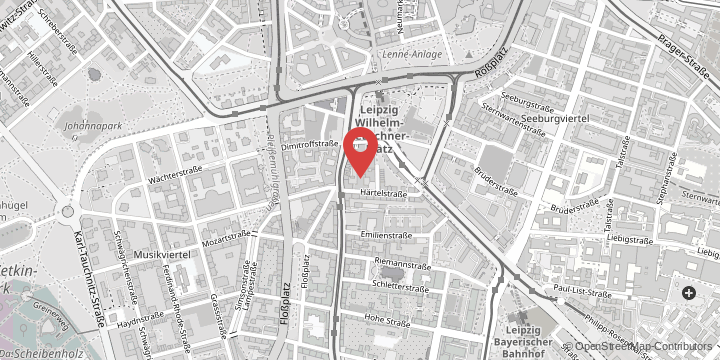

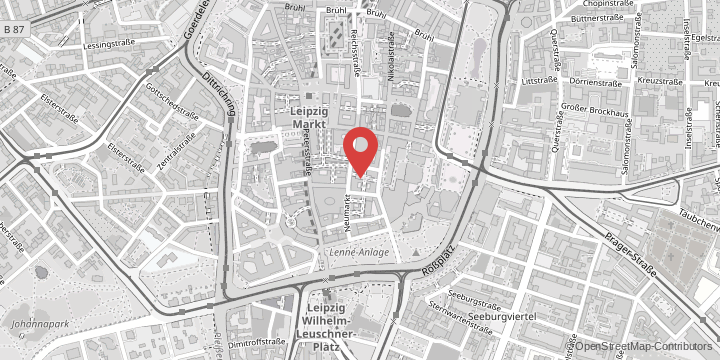

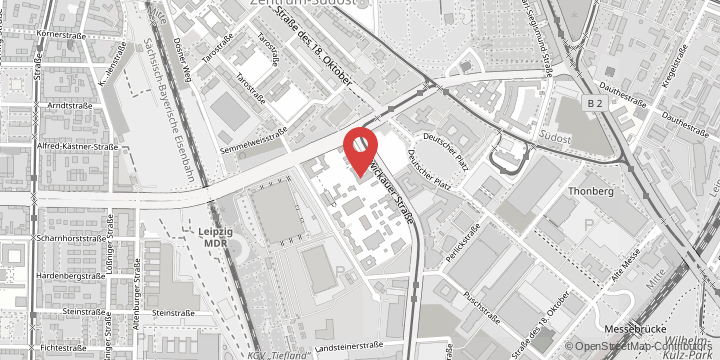

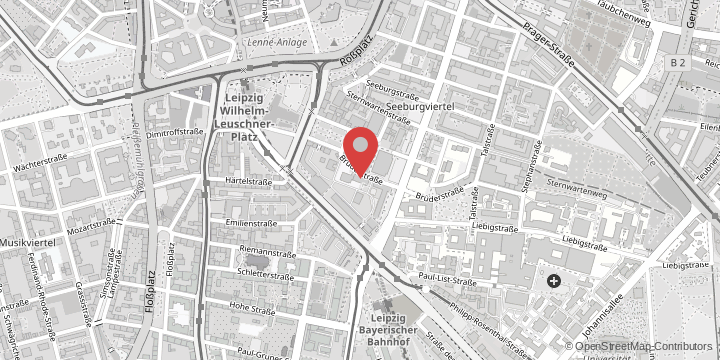

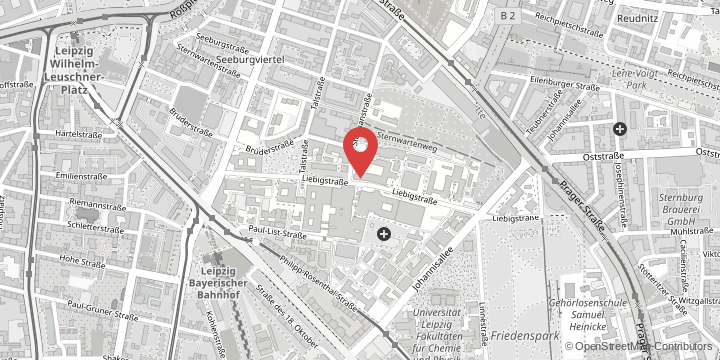

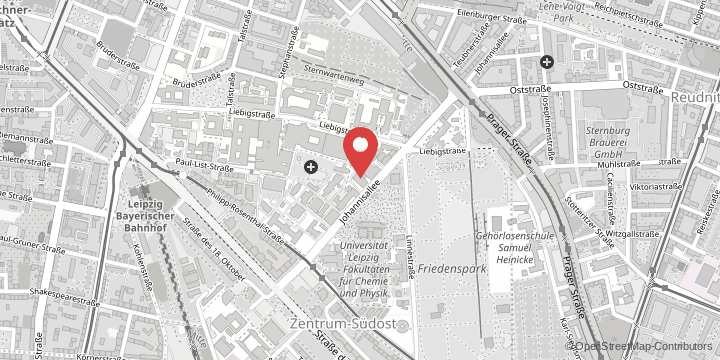

“The higher-than-expected economic outputs of larger cities critically depend on the extreme outcomes of the successful few. Ignoring this dependency, policy makers risk overestimating the stability of urban growth, particularly in the light of the high spatial mobility among urban elites and their movement to where the money is,” says Marc Keuschnigg, associate professor at the Institute for Analytical Sociology at Linköping University and professor at the Institute of Sociology at Leipzig University.

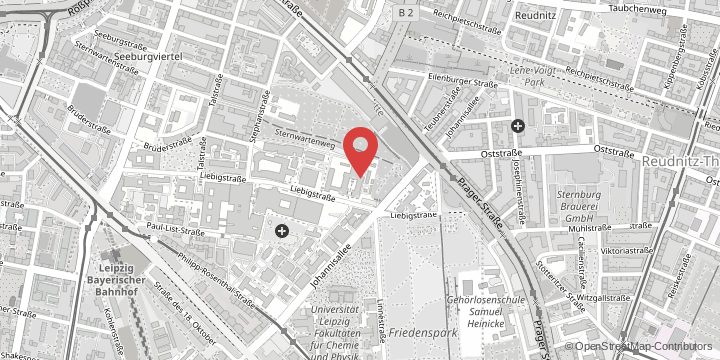

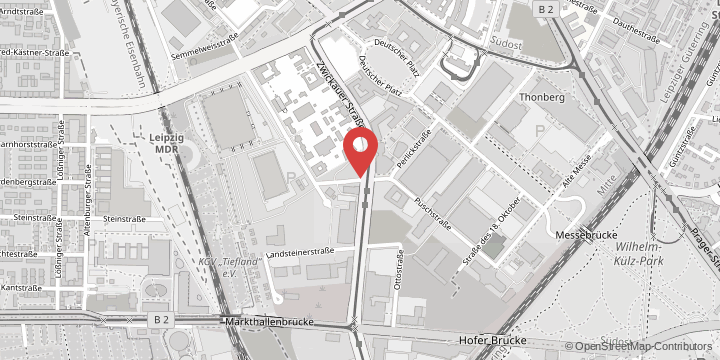

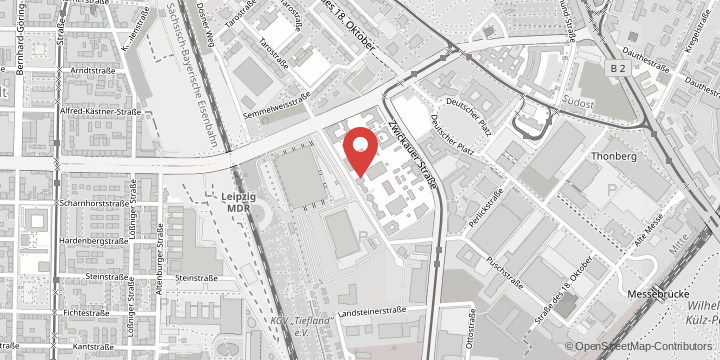

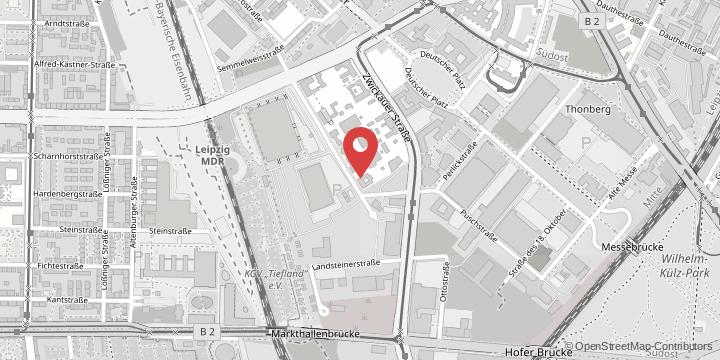

In a study published in Nature Human Behaviour, the researchers analyse geocoded micro-data on social interactions and economic output in Sweden, Russia, and the United States. They show that inequality is rampant in earnings and innovation, as well as in measures of urban interconnectivity.

An individual’s productivity depends on the local social environments in which they find themselves. Because of the greater diversity in larger cities, skilled and specialized people are more likely to find others whose skills are complementary to their own. This allows for higher levels of productivity and greater learning opportunities in larger cities.

But, not everyone can access the productive social environments that larger cities provide. Different returns from context accumulate over time, which gives rise to substantial inequality.

The researchers traced 1.4 million Swedish wage earners over time and found that those who were initially successful in large cities flourished to a greater extent than the successful in smaller cities. By contrast, the typical individuals in both smaller and larger cities experienced almost identical wage trajectories.

Consequently, the initially successful individuals in the bigger cities increasingly distanced themselves from both the typical individual in their own city, creating inequality within the big cities, and the most successful individuals in smaller cities, creating inequality between cities.

The study also finds that top earners are more likely to leave smaller city than larger ones, and that these overperformers tend overwhelmingly to move to the largest cities. The disproportionate out-migration of the most successful individuals from smaller cities results in a reinforcement process that takes away many of the most promising people in less populous regions while adding them to larger cities.

The biggest cities are buzzing because they also host the most innovative, sociable, and skilled people. These outliers add disproportionately to city outputs – a ‘the rich get richer’ process that brings cumulative advantage to the biggest cities.

From a policy perspective, the study considers the sustainability of city life against the backdrop of rising urban inequality.

“Urban science has largely focused on city averages. The established approach just looked at one data point per city, for example average income. With their focus on averages, prior studies overlooked the stark inequalities that exist within cities when making predictions about how urban growth affects the life experiences of city dwellers,” says Marc Keuschnigg.

With respect to urban inequality, the study draws attention to the partial exclusion of most city dwellers from the socioeconomic benefits of growing cities. Their lifestyle, different than among the urban elite, benefits less from geographical location. When accounting for the cost of living in larger cities, many big-city dwellers will in fact be worse off as compared to similar people living in smaller places.

The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council.